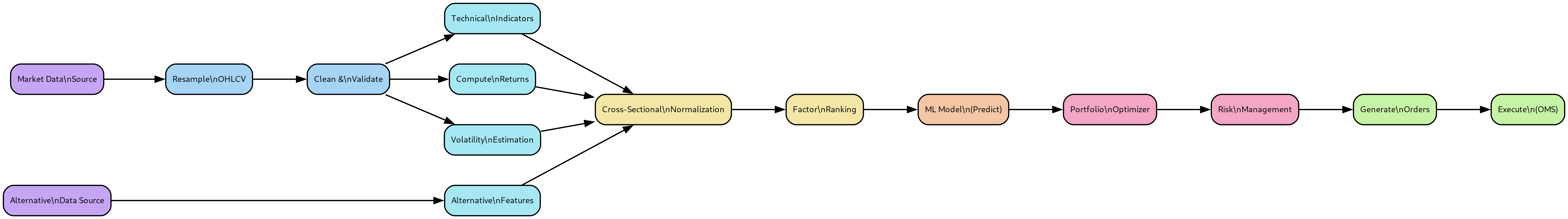

same DAG can be run in a Jupyter notebook for research and experimentation or in a production script, without any change in code. (15) Python data science stack support. Data science libraries (such as Pandas, numpy, scipy, sklearn) are supported natively to describe computation. The framework comes with a library of pre-built nodes for many ML/AI applications. 1.1. The fallacy of finite data in data science. Traditional data science workflows operate under a fundamental assumption that data is finite and complete. The canonical workflow reads a fixed dataset as input, constructs a model through training procedures, and generates output predictions. This paradigm conceptualizes data as a static, bounded entity of known and finite size that can be loaded entirely into memory or processed in a single pass. This assumption represents a significant departure from real-world data generation processes. Most production systems encounter unbounded data that arrives incrementally over time as a continuous stream. Time-series data sources-including sensor measurements, financial transactions, and system logs-generate observations continuously. Such data streams exhibit no natural termination point and grow indefinitely over operational lifetimes. The standard approach to reconciling unbounded data with finite-data processing frameworks partitions the continuous data stream into discrete chunks (typically referred to as "batches") and applies modeling and transformation logic to each chunk independently. This discretization strategy, while pragmatic, introduces several categories of technical challenges: (1) Batch boundary artifacts. Discretizing continuous streams into finite batches creates artificial discontinuities at batch boundaries. Operations that require temporal context across these boundaries-such as rolling statistics, cumulative aggregations, or stateful transformations-may yield results that depend on the specific partitioning scheme employed. This dependence on batch structure can lead to discrepancies between batch-mode development results and streaming-mode production behavior, complicating model validation and deployment verification. (2) Causality violations. Batch processing frameworks typically provide simultaneous access to all observations within a batch. This temporal indiscriminacy facilitates inadvertent causality violations, where computations at time t access observations from time t ′ > t. Such violations manifest as data leakage during model development and result in systematic prediction failures when deployed in real-time environments where future observations are genuinely unavailable. Detection of these causality errors during development requires explicit validation infrastructure that many batch-oriented frameworks do not provide. (3) Development-production implementation divergence. Batch processing frameworks often lack native support for streaming execution semantics. Consequently, models prototyped using batch-oriented tools (e.g., pandas, scikit-learn) frequently require substantial reimplementation for production deployment in streaming environments. This translation process introduces both development overhead and the risk of semantic discrepancies between research prototypes and production implementations, potentially leading to unexpected behavioral differences in deployed systems. (4) Limited reproducibility of production failures. Production failures in real-time systems often depend on precise temporal ordering and timing of data arrivals. Batch-based development frameworks typically abstract away these temporal details, making faithful reproduction of production failures in development environments challenging. Without the ability to replay exact event sequences with accurate timing semantics, systematic debugging of production issues becomes significantly more difficult. DataFlow addresses these challenges through a unified computational model that treats data as unbounded streams and enforces strict causality via point-in-time idempotency guarantees (see

DataFlow is a framework to build, test, and deploy high-performance streaming computing systems based on machine learning and artificial intelligence.

The goal of DataFlow is to increase the productivity of data scientists by empowering them to design and deploy systems with minimal or no intervention from data engineers and devops support.

Guiding desiderata in the design of DataFlow include:

(1) Support rapid and flexible prototyping with the standard Python/Jupyter/data science tools (2) Process both batch and streaming data in exactly the same way (3) Avoid software rewrites in going from prototype to production (4) Make it easy to replay stream events in testing and debugging (5) Specify system parameters through config (6) Scale gracefully to large data sets and dense compute These design principles are embodied in the many design features of DataFlow, which include:

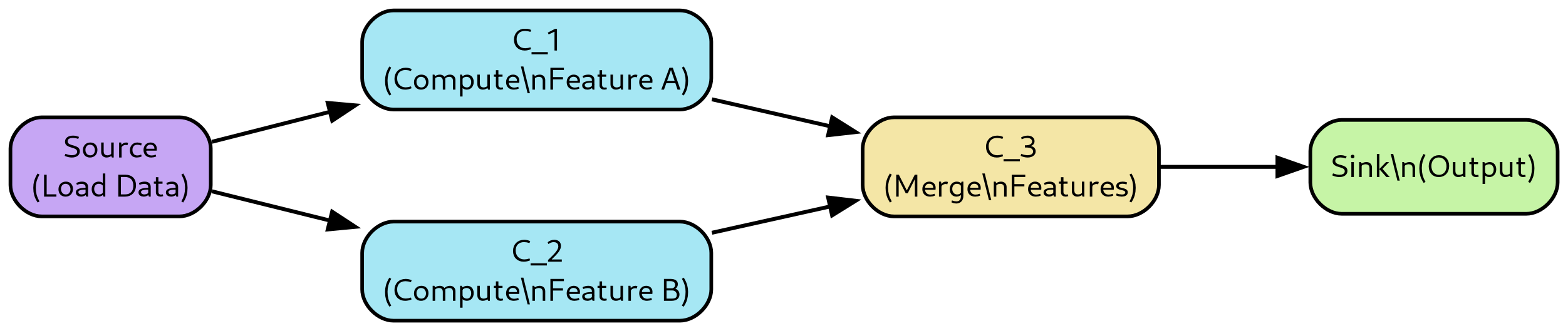

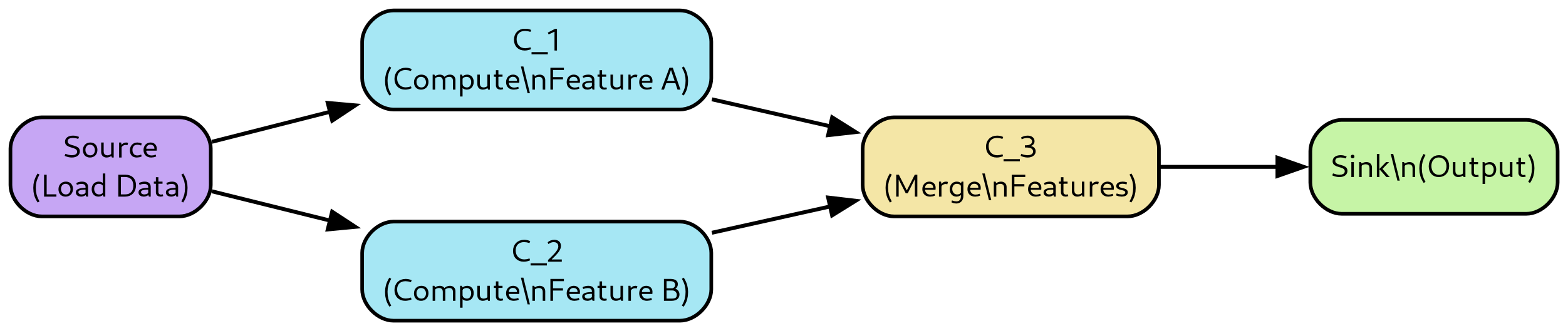

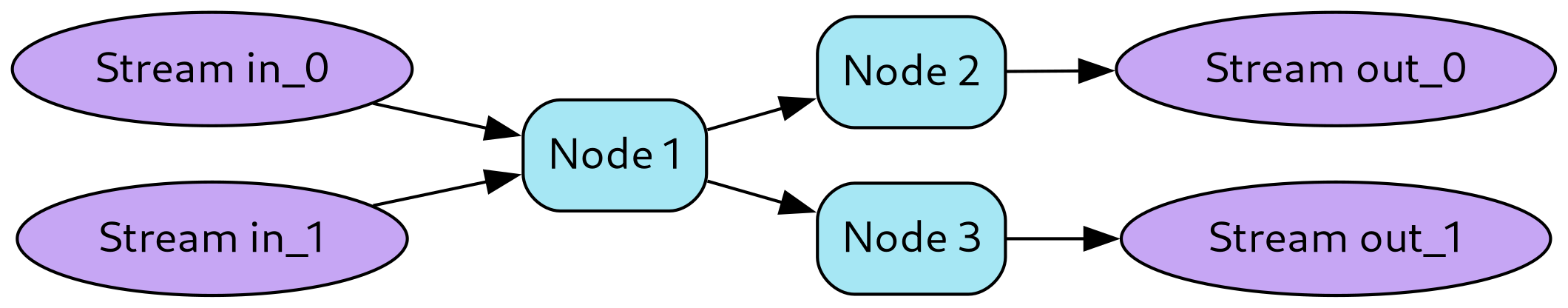

(1) Computation as a direct acyclic graph. DataFlow represents models as direct acyclic graphs (DAG), which is a natural form for dataflow and reactive models typically found in real-time systems. Procedural statements are also allowed inside nodes. (2) Time series processing. All DataFlow components (such as data store, compute engine, deployment) handle time series processing in a native way. Each time series can be univariate or multivariate (e.g., panel data) represented in a data frame format.

(3) Support for both batch and streaming modes. The framework allows running a model both in batch and streaming mode, without any change in the model representation.

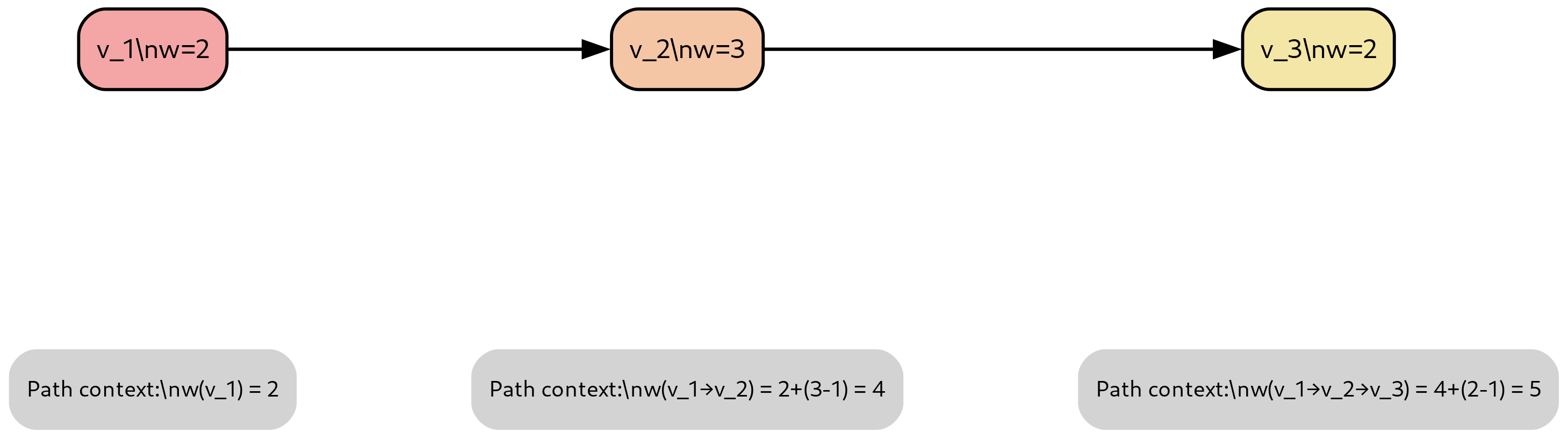

The same compute graph can be executed feeding data in one shot or in chunks (as in historical/batch mode), or as data is generated (as in streaming mode). DataFlow guarantees that the model execution is the same independently on how data is fed, as long as the model is strictly causal. Testing frameworks are provided to compare batch/streaming results so that any causality issues may be detected early in the development process. (4) Precise handling of time. All components automatically track the knowledge time of when the data is available at both their input and output. This allows one to easily catch future peeking bugs, where a system is non-causal and uses data available in the future. (5) Observability and debuggability. Because of the ability to capture and replay the execution of any subset of nodes, it is possible to easily observe and debug the behavior of a complex system. (6) Tiling. DataFlow’s framework allows streaming data with different tiling styles (e.g., across time, across features, and both), to minimize the amount of working memory needed for a given computation, increasing the chances of caching computation. (7) Incremental computation and caching. Because the dependencies between nodes are explicitly tracked by DataFlow, only nodes that see a change of inputs or in the implementation code need to be recomputed, while the redundant computation can be automatically cached. (8) Maximum parallelism. Because the computation is expressed as a DAG, the DataFlow execution scheduler can extract the maximum amount of parallelism and execute multiple nodes in parallel in a distributed fashion, minimizing latency and maximizing throughput of a computation. (9) Automatic vectorization. DataFlow DAG nodes can apply a computation to a crosssection of features relying on numpy and Pandas vectorization. (10) Support for train/prediction mode. A DAG can be run in ‘fit’ mode to learn some parameters, which are stored by the relevant DAG nodes, and then run in ‘predict’ mode to use the learned parameters to make predictions. This mimics the Sklearn semantic.

There is no limitation to the number of evaluation phases that can be created (e.g., train, validation, prediction, save state, load state). Many different learning styles are supported from different types of runners (e.g., in-sample-only, in-sample vs out-of-sample, rolling learning, cross-validation). (11) Model serialization. A fit DAG can be serialized to disk and then materialized for prediction in production. (12) Configured through a hierarchical configuration. Each parameter in a DataFlow system is controlled by a corresponding value in a configuration. In other words, the config space is homeomorphic with the space of DataFlow systems: each config corresponds to a unique DataFlow system, and vice versa, each DataFlow sytem is completely represented by a Config. A configuration is represented as a nested dictionary following the same structure of the DAG to make it easy to navigate its structure. This makes it easy to create an ensemble of DAGs sweeping a multitude of parameters to explore the design space. (13) Deployment and monitoring. A DataFlow system can be deployed as a Docker container. Even the development system is run as a Docker container, supporting the development and testing of systems on both cloud (e.g., AWS) and local desktop. Airflow is used to schedule and monitor long-running DataFlow

This content is AI-processed based on open access ArXiv data.