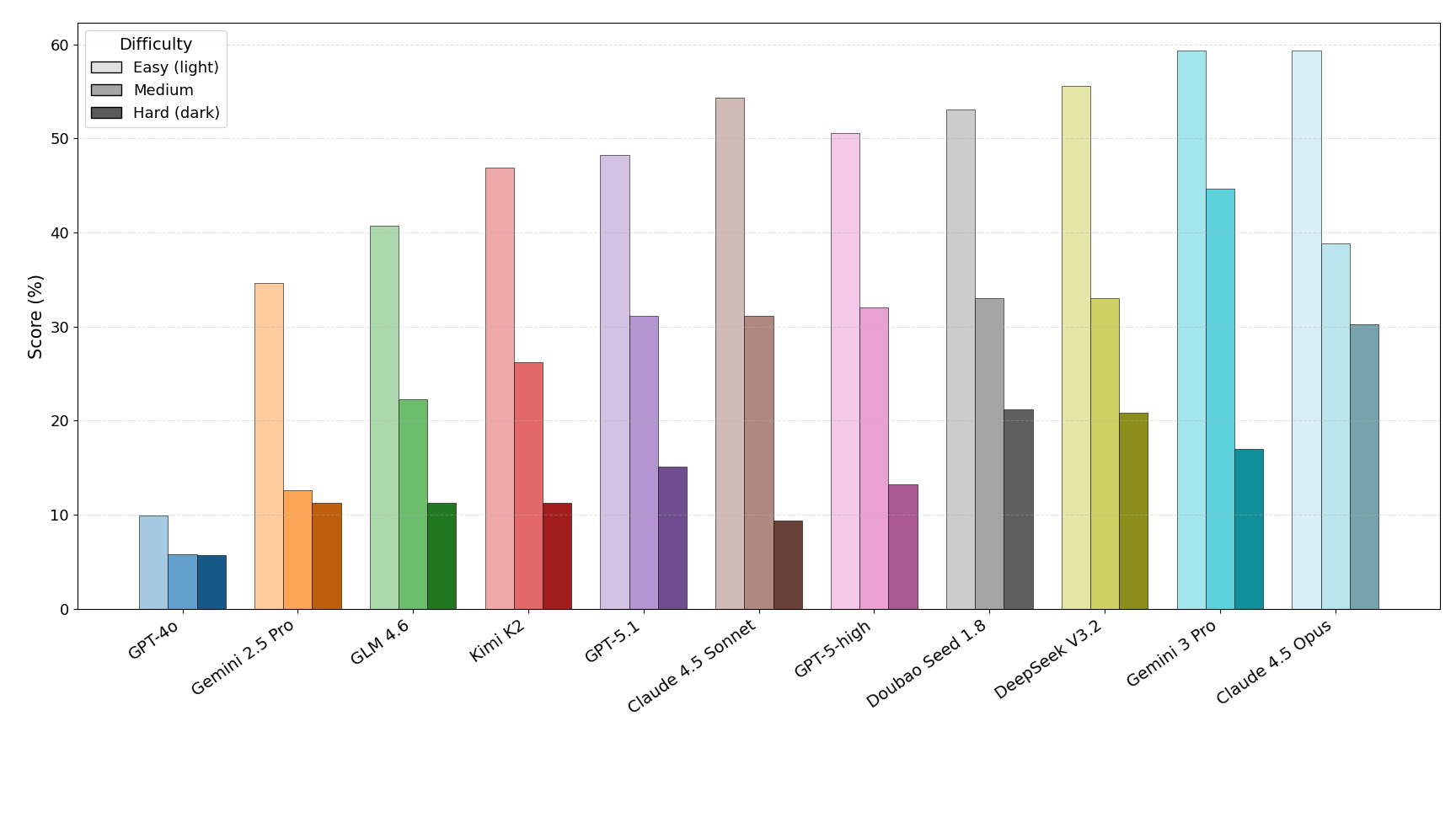

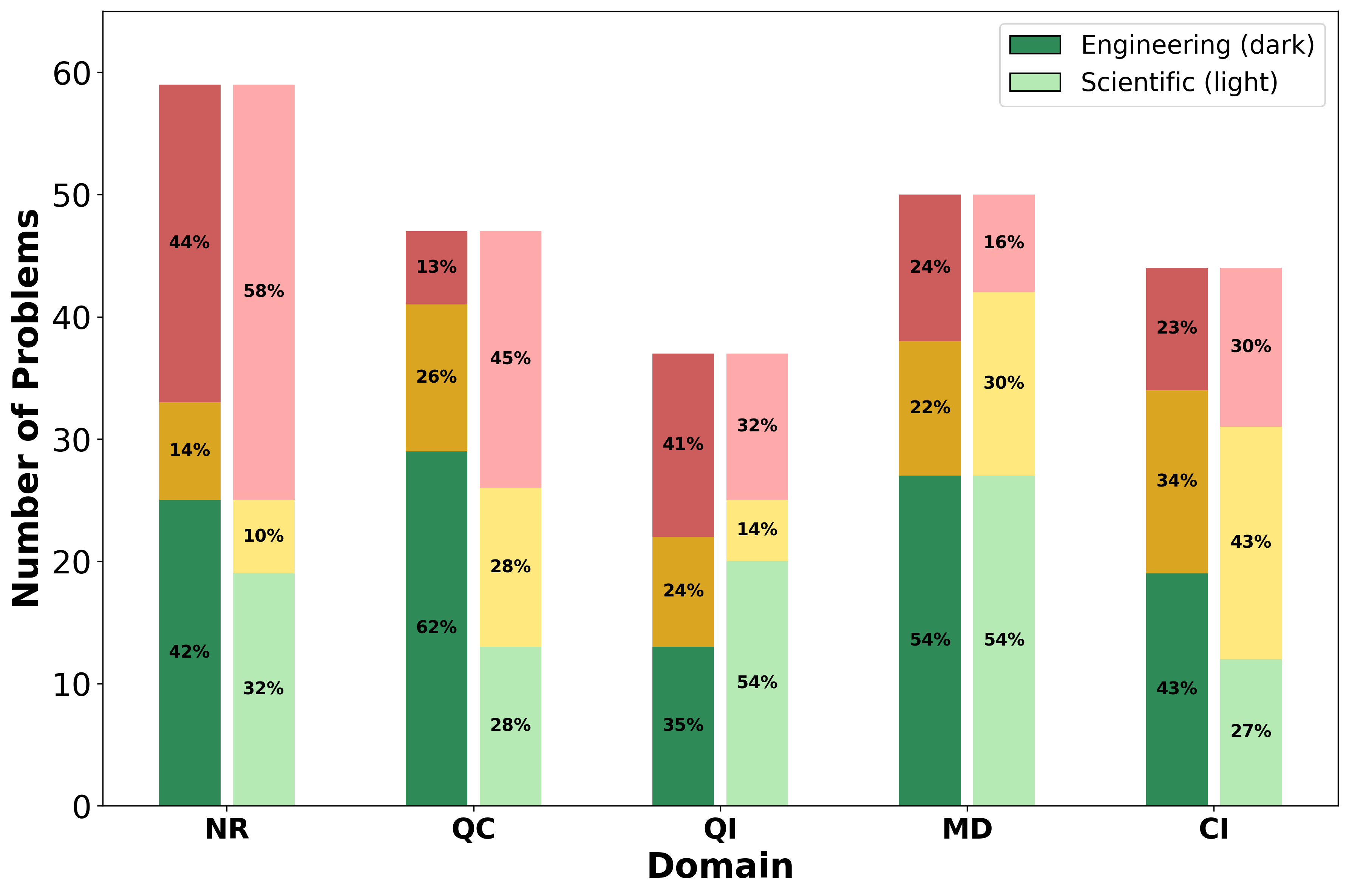

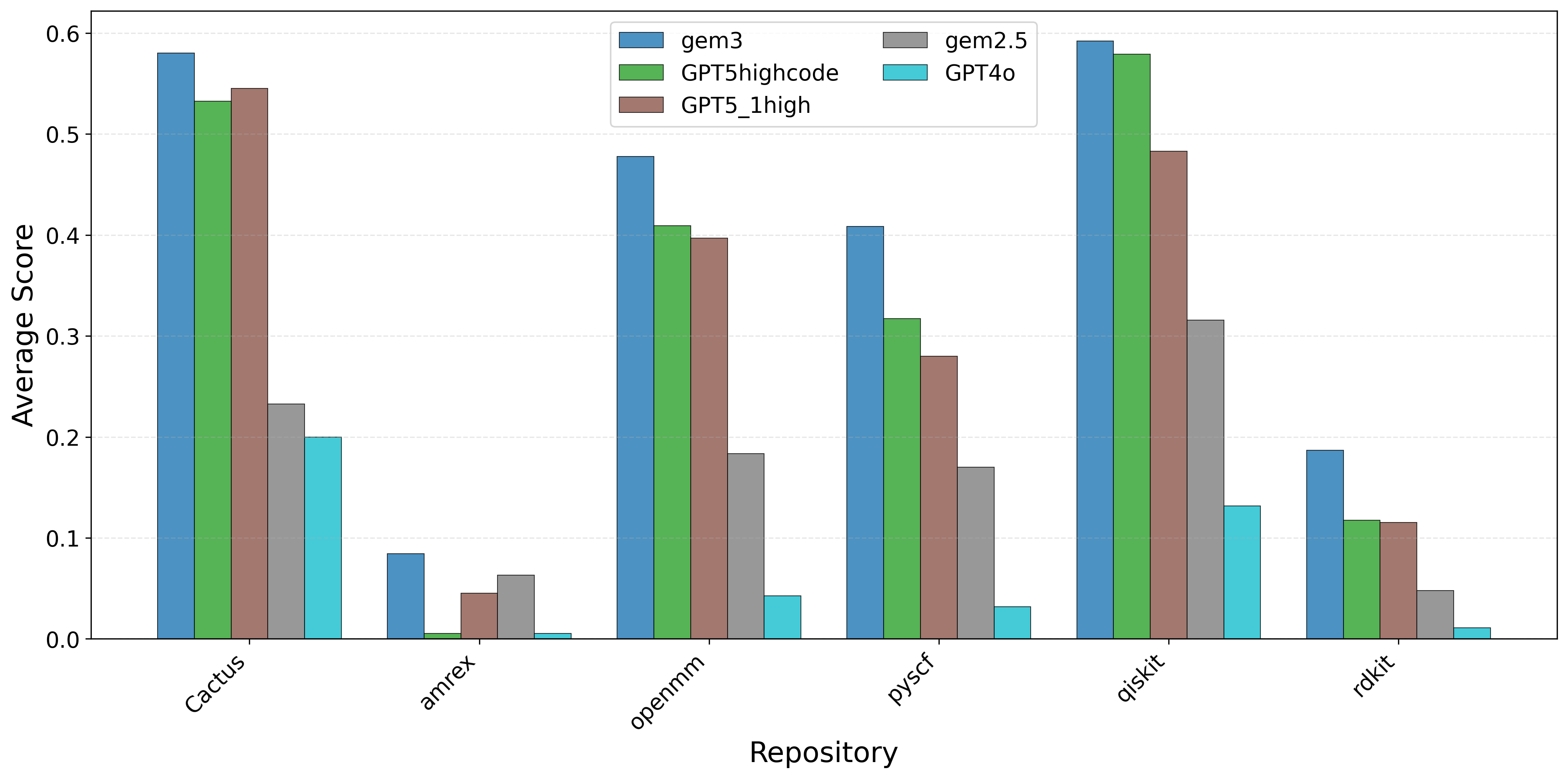

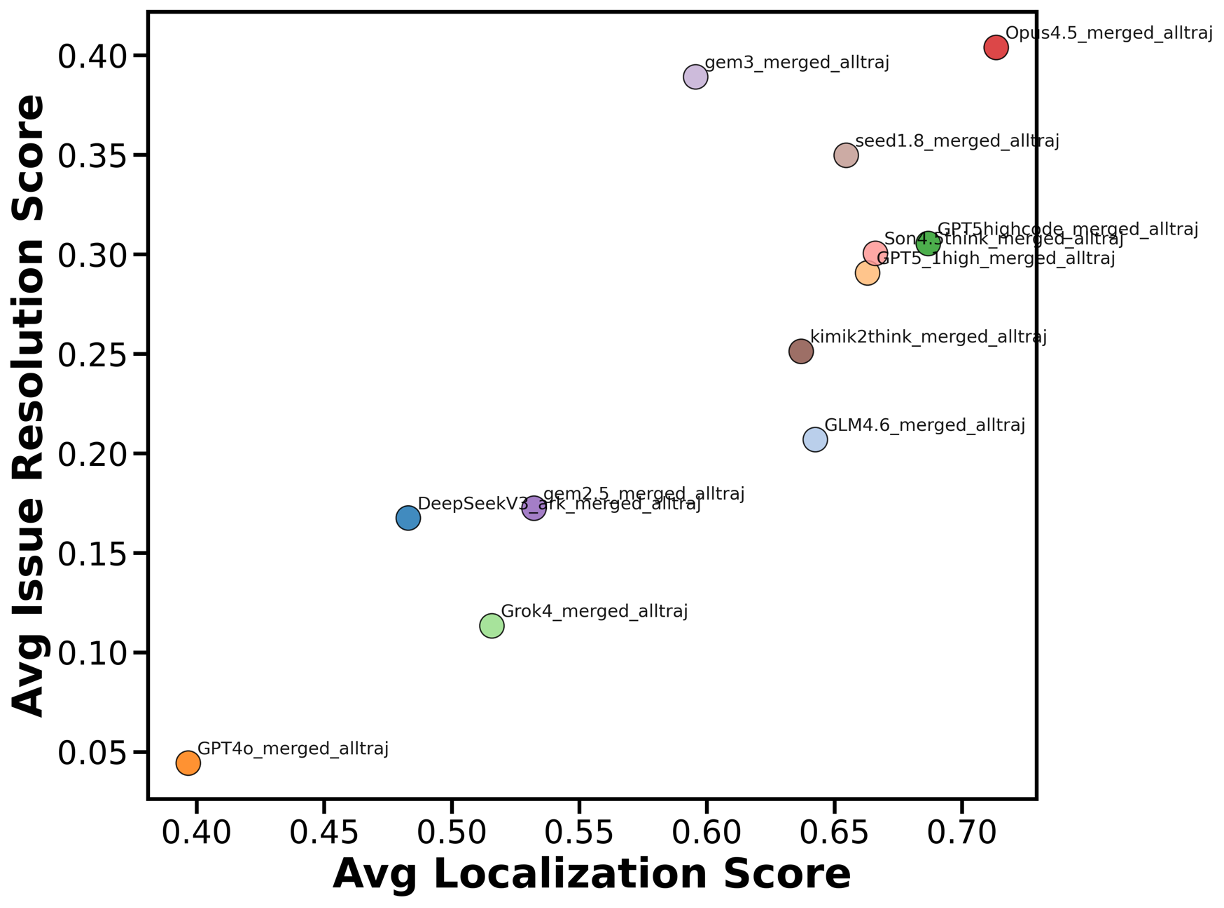

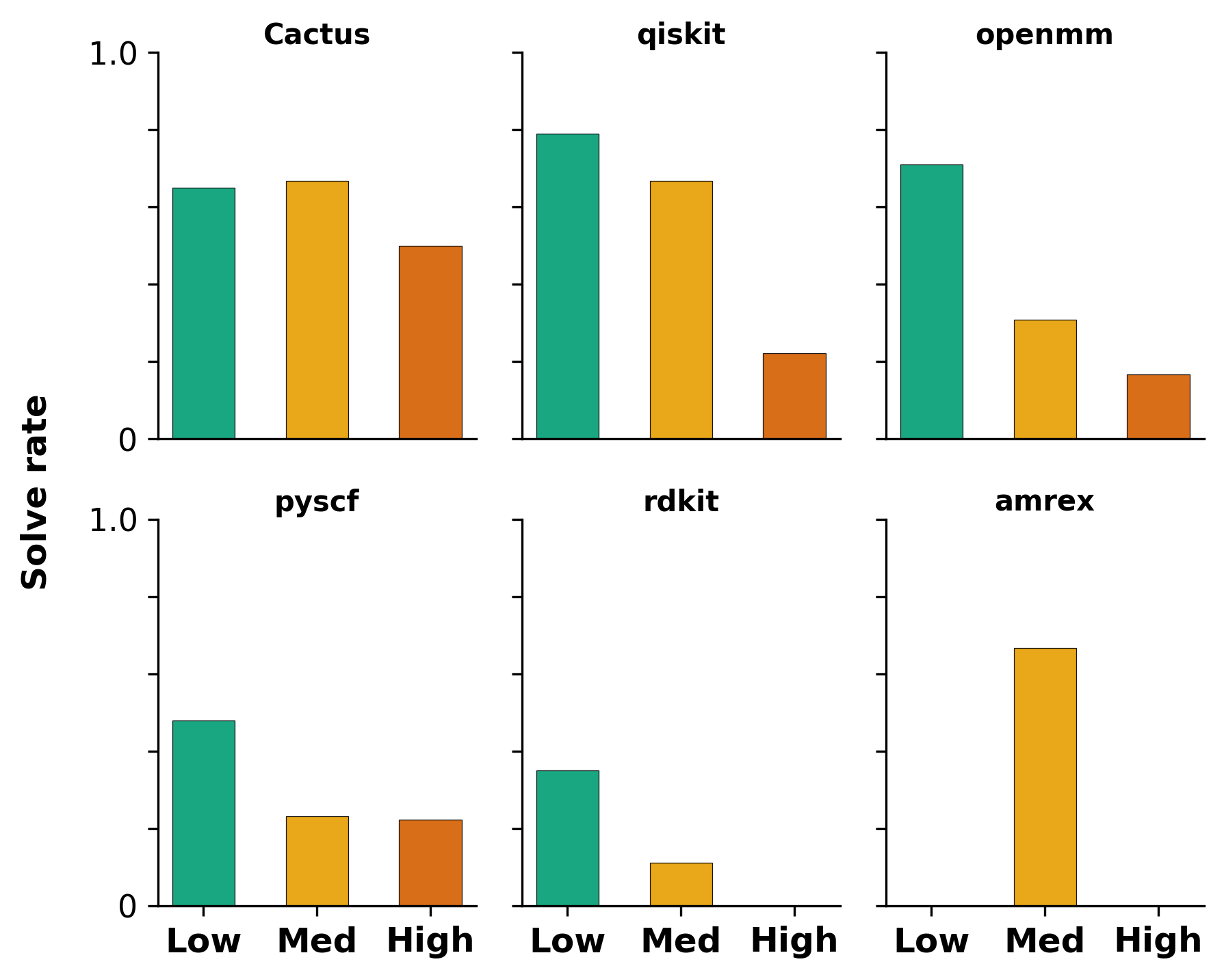

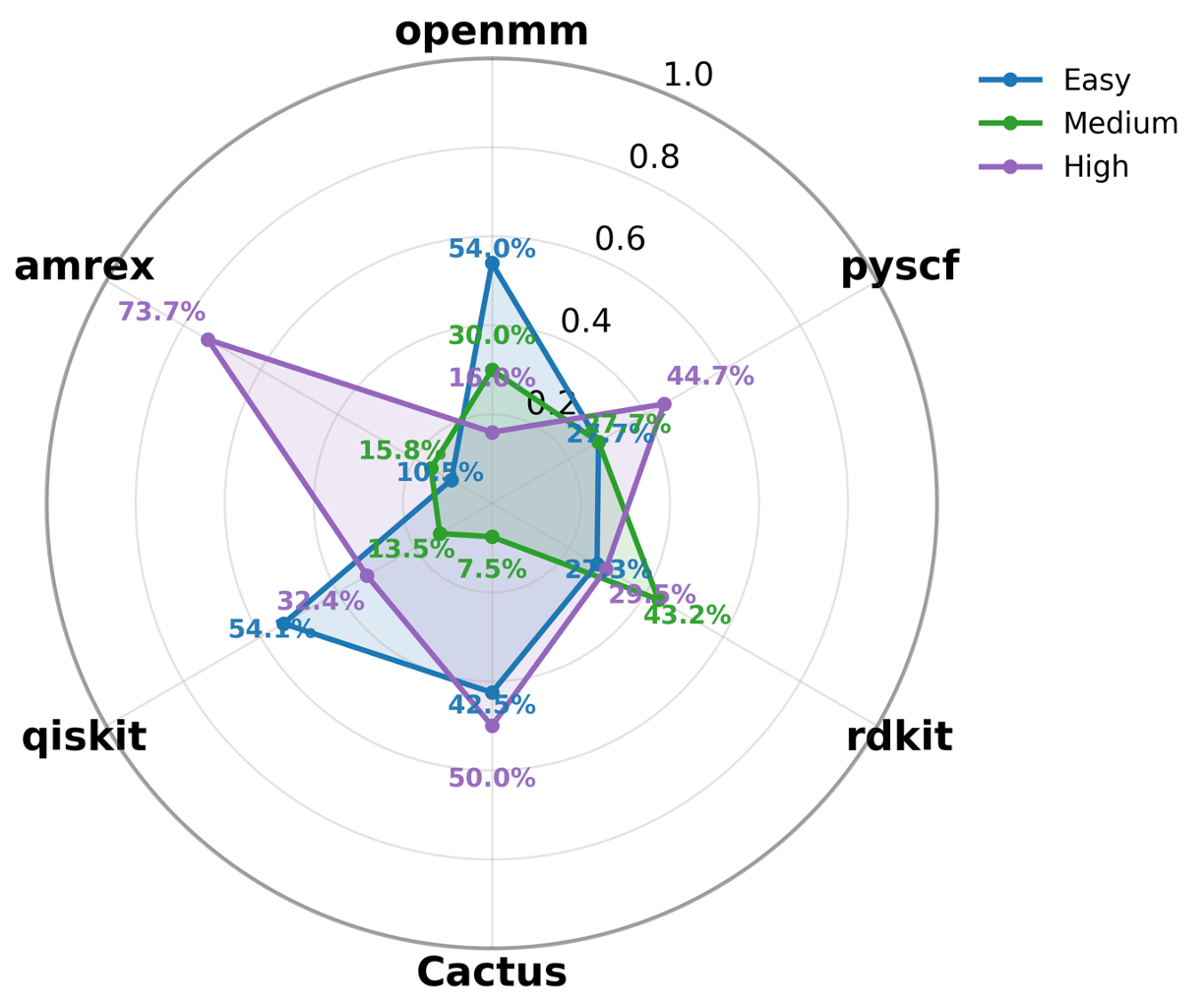

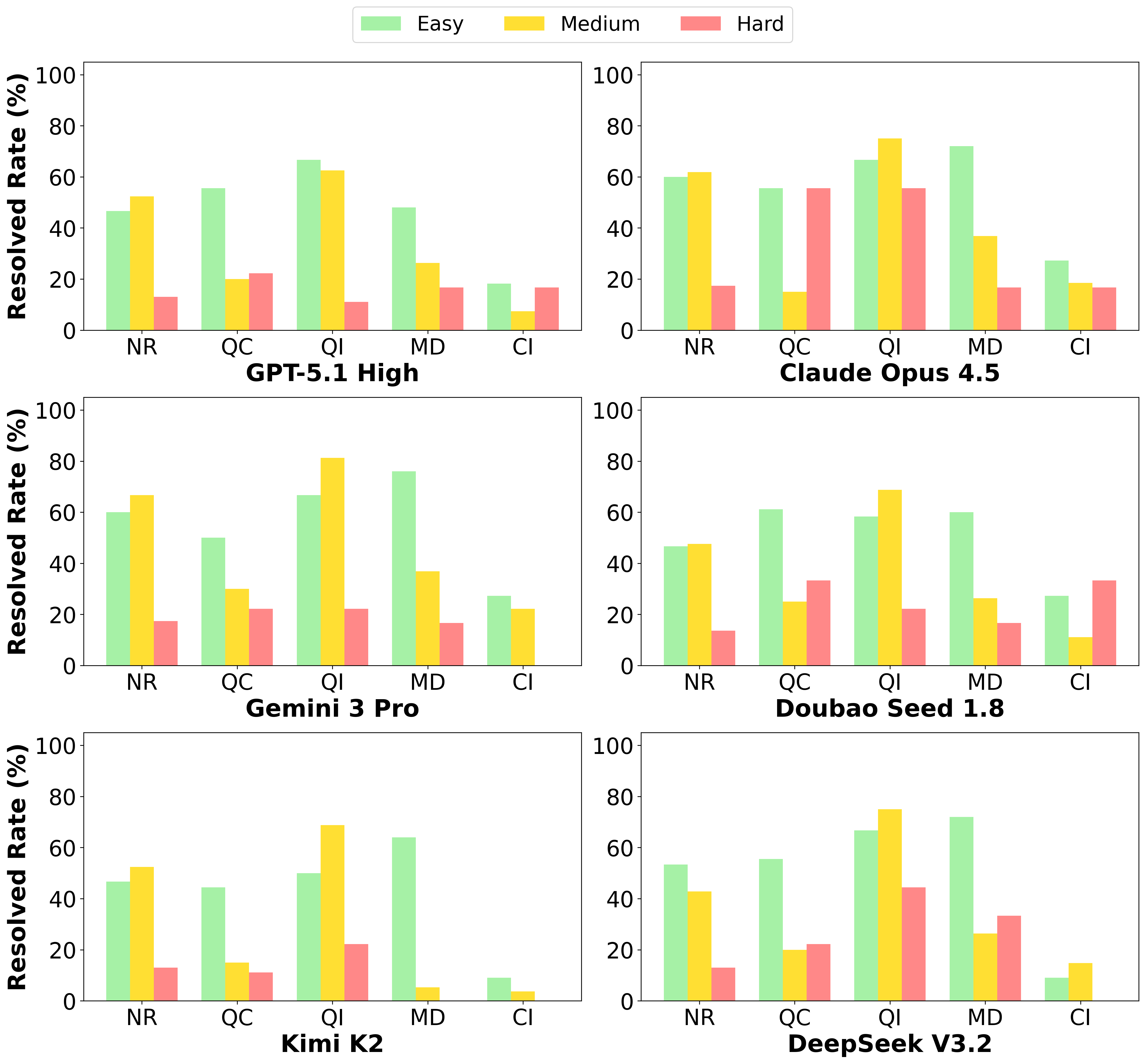

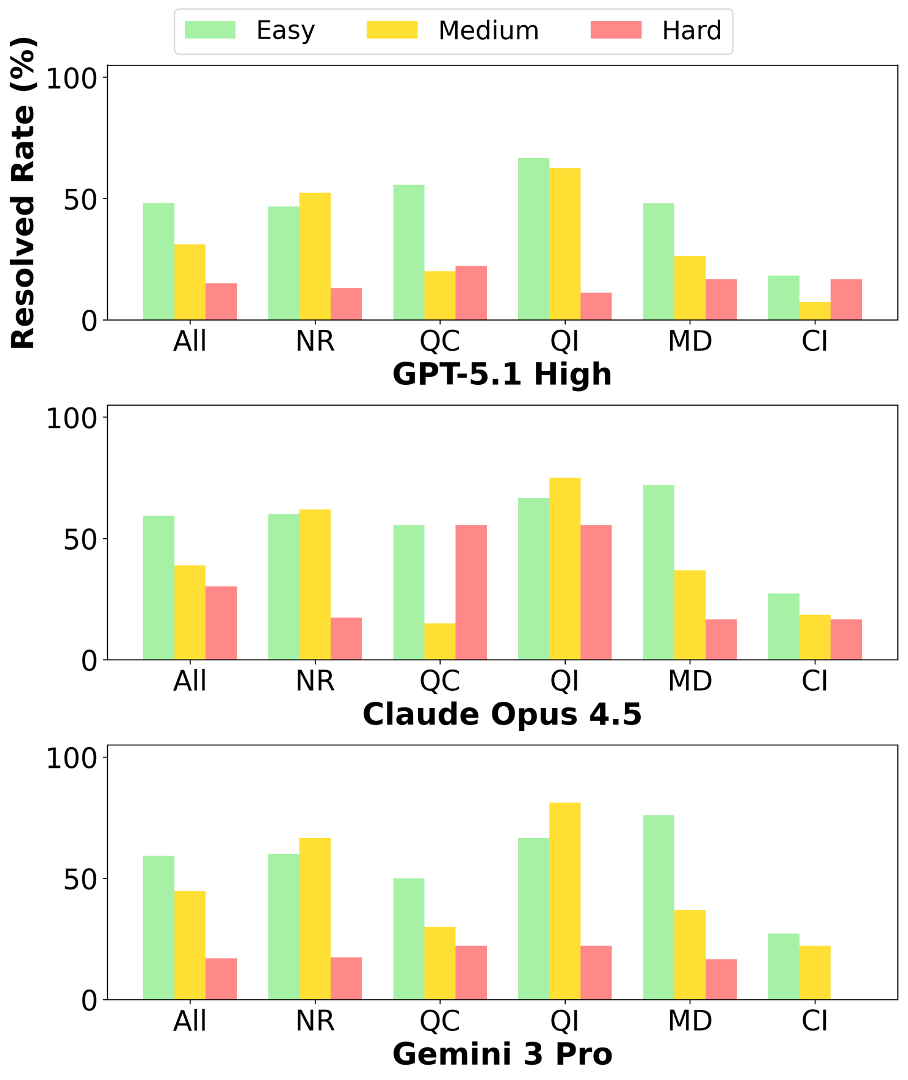

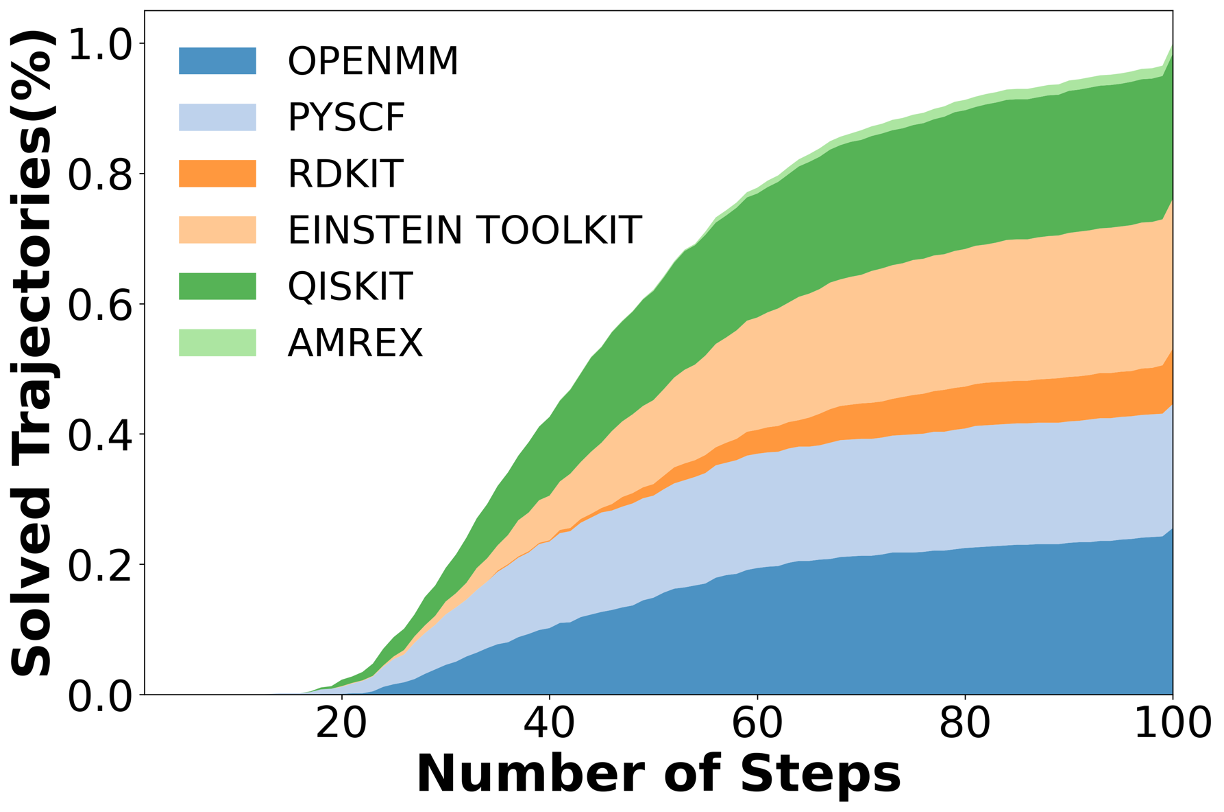

We introduce AInsteinBench, a large-scale benchmark for evaluating whether large language model (LLM) agents can operate as scientific computing development agents within real research software ecosystems. Unlike existing scientific reasoning benchmarks which focus on conceptual knowledge, or software engineering benchmarks that emphasize generic feature implementation and issue resolving, AInsteinBench evaluates models in end-to-end scientific development settings grounded in production-grade scientific repositories. The benchmark consists of tasks derived from maintainer-authored pull requests across six widely used scientific codebases, spanning quantum chemistry, quantum computing, molecular dynamics, numerical relativity, fluid dynamics, and cheminformatics. All benchmark tasks are carefully curated through multi-stage filtering and expert review to ensure scientific challenge, adequate test coverage, and well-calibrated difficulty. By leveraging evaluation in executable environments, scientifically meaningful failure modes, and test-driven verification, AInsteinBench measures a model's ability to move beyond surface-level code generation toward the core competencies required for computational scientific research.

Modern scientific discovery is increasingly mediated by large-scale computational systems. Across disciplines such as chemistry, physics, and materials science, new scientific insights are no longer derived solely from analytical derivations or isolated simulations, but from sustained interaction with complex scientific software ecosystems. Researchers routinely formulate hypotheses, encode physical or mathematical assumptions into simulation code, and iteratively refine implementations based on empirical feedback from tests, solvers, and large-scale simulation runs. As illustrated in Figure 2, such a workflow follows an iterative cycle of reading literature, experimenting, and solving questions, with active interactions with the environment: the academic institution and compute infrastructure. In this setting, scientific discoveries depend not only on the literal understanding of the subject, but also on the ability to implement the theory into production codebases and execute in mass production.

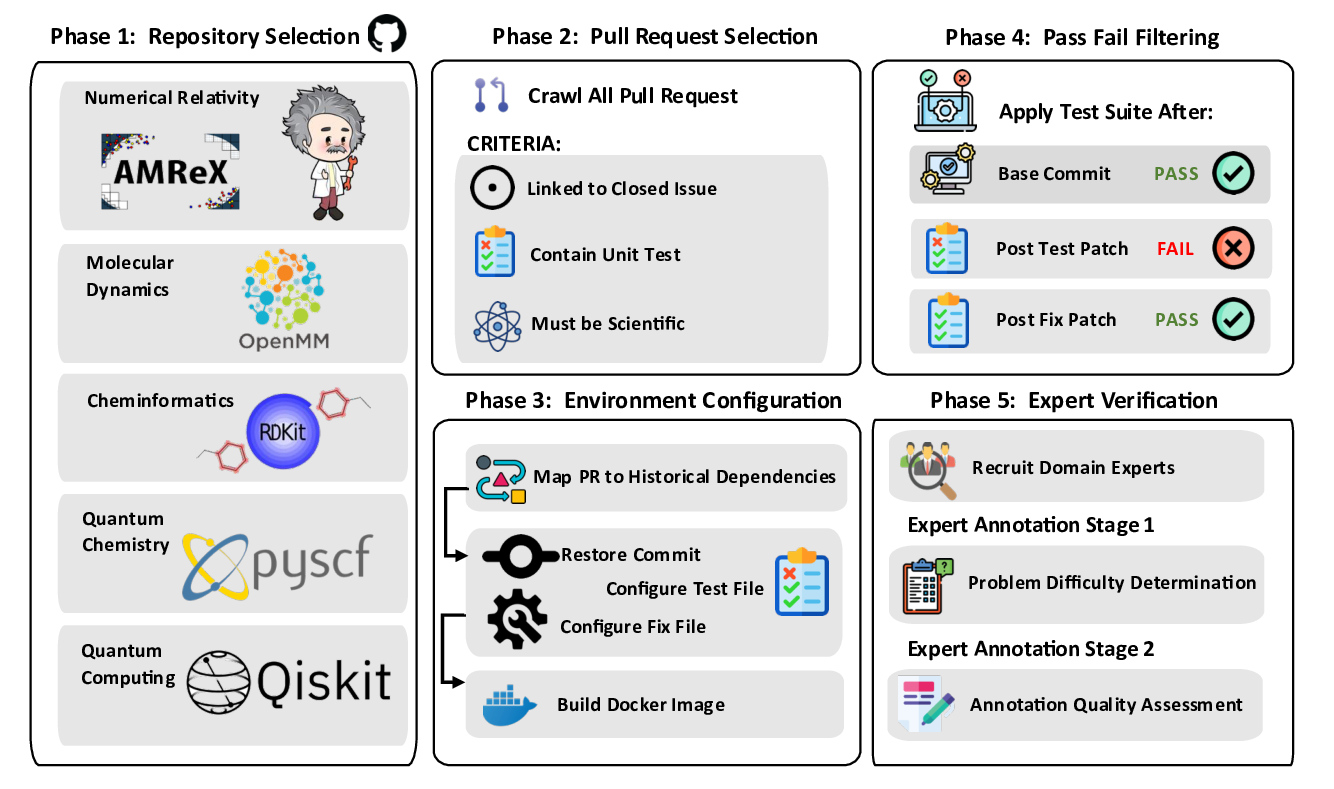

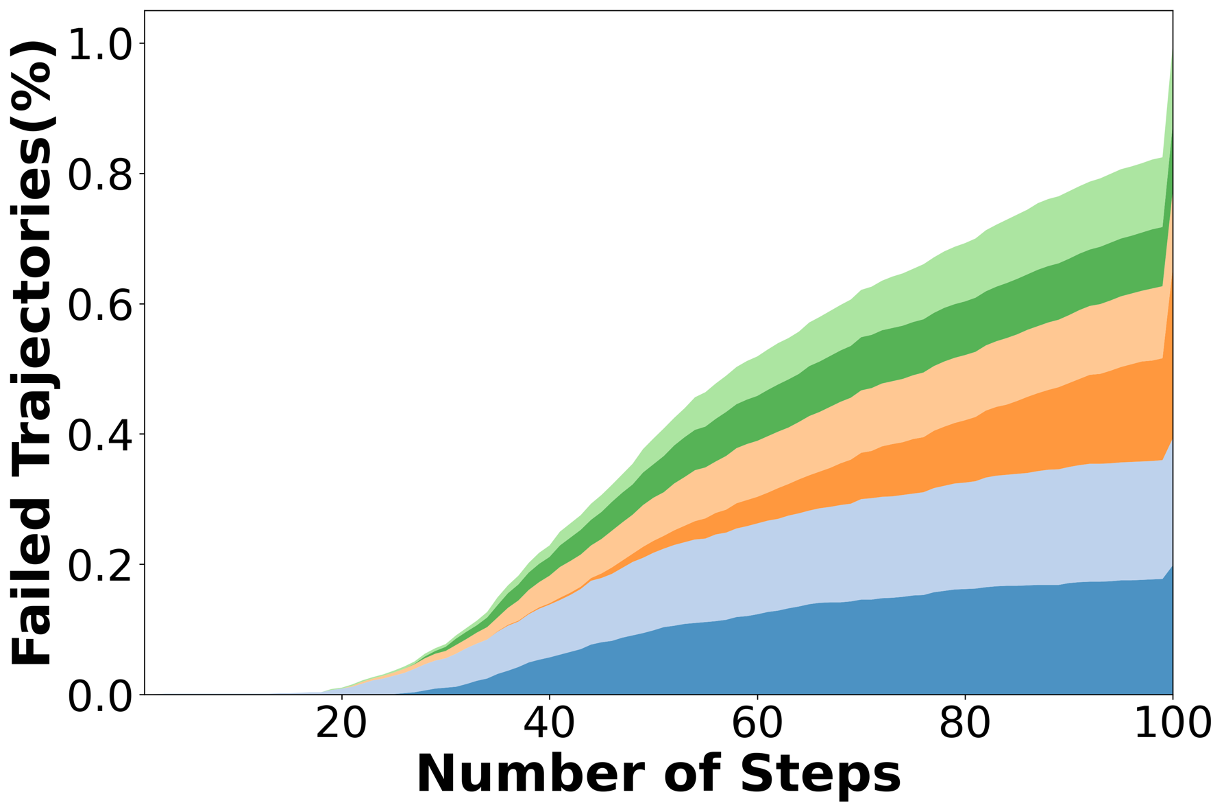

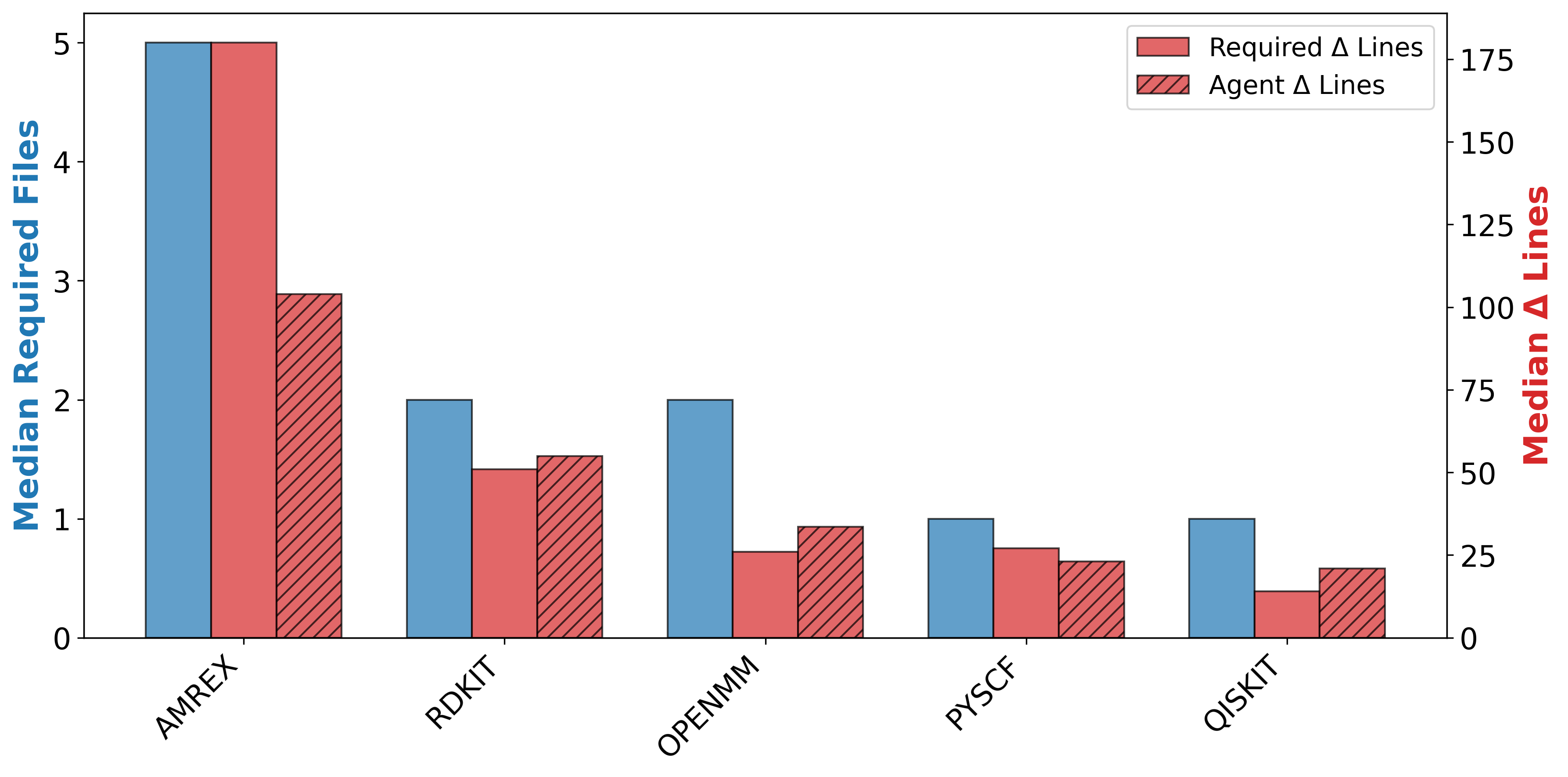

Recent advances in large language models (LLMs) have growing interest in their potential to assist scientific computing research [1][2][3]. To function as genuine research assistants, LLM-based agents must be able to navigate long-lived scientific repositories, understand domain-specific invariants and numerical constraints, and implement or debug code in ways that preserve scientific correctness. Whether current models are capable of the transition from surface-level scientific reasoning toward more analytic and physically based reasoning remains an open question. As shown in Fig. 2, analogous to human researchers, the LLM agents engage in a workflow of loading files into context, executing bash commands, and committing changes, with active interaction with its environment: usually a Docker container we built.

Current scientific reasoning benchmarks evaluate high-level conceptual understanding [4][5][6][7][8] or isolated coding questions [9], but they stop short of requiring LLMs to navigate, interpret, and modify real scientific repositories. As a result, these benchmarks fundamentally underrepresent the skills needed to be a successful scientist. Across nearly all of academia, there are numerous groups whose primary workflow entails developing ideas within large scientific repositories. This is no better demonstrated than by looking through the author lists of popular scientific repositories [10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18]. Existing SWE benchmarks [19,20] are not much better, as they do not reflect the coding paradigms, numerical stability constraints, cross-language heterogeneity, and HPC execution environments that dominate scientific computing. Although SWE-bench includes one scientific repository, Astropy, this is by no means a representative sampling. As a result, a fundamental gap remains: no benchmark currently measures an LLM’s ability to solve issue or write new features through patch synthesis inside real, large-scale scientific software ecosystems.

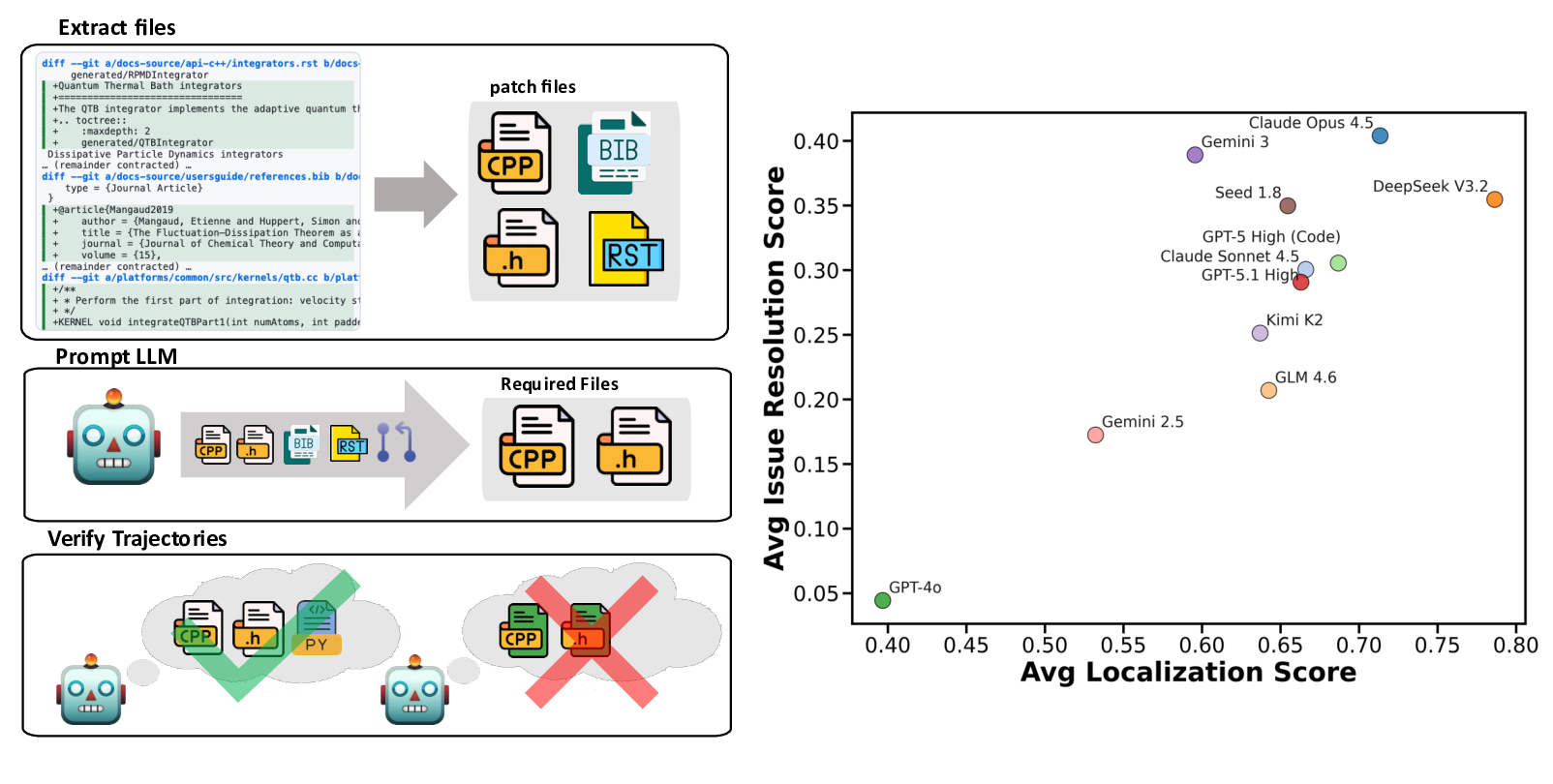

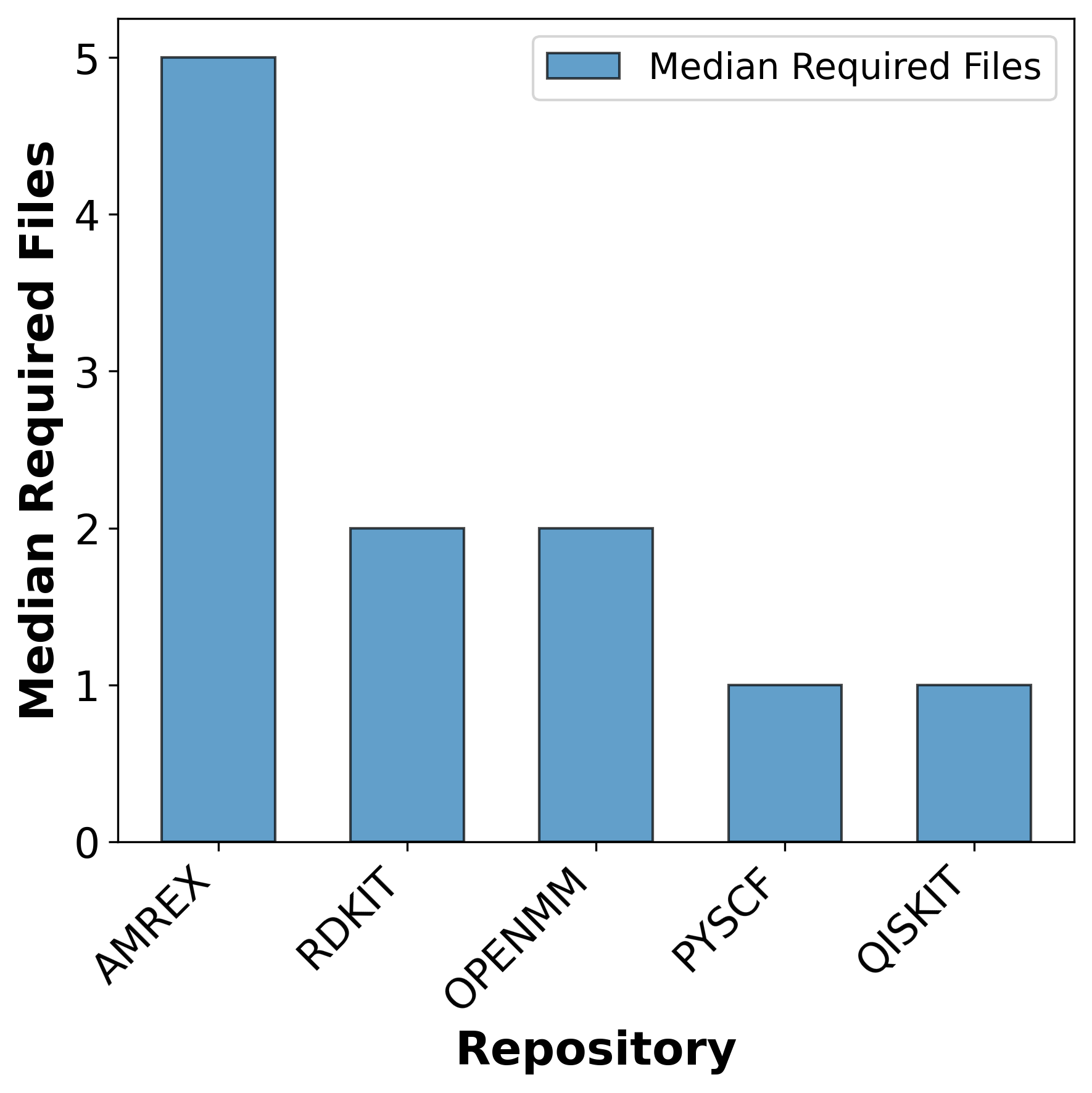

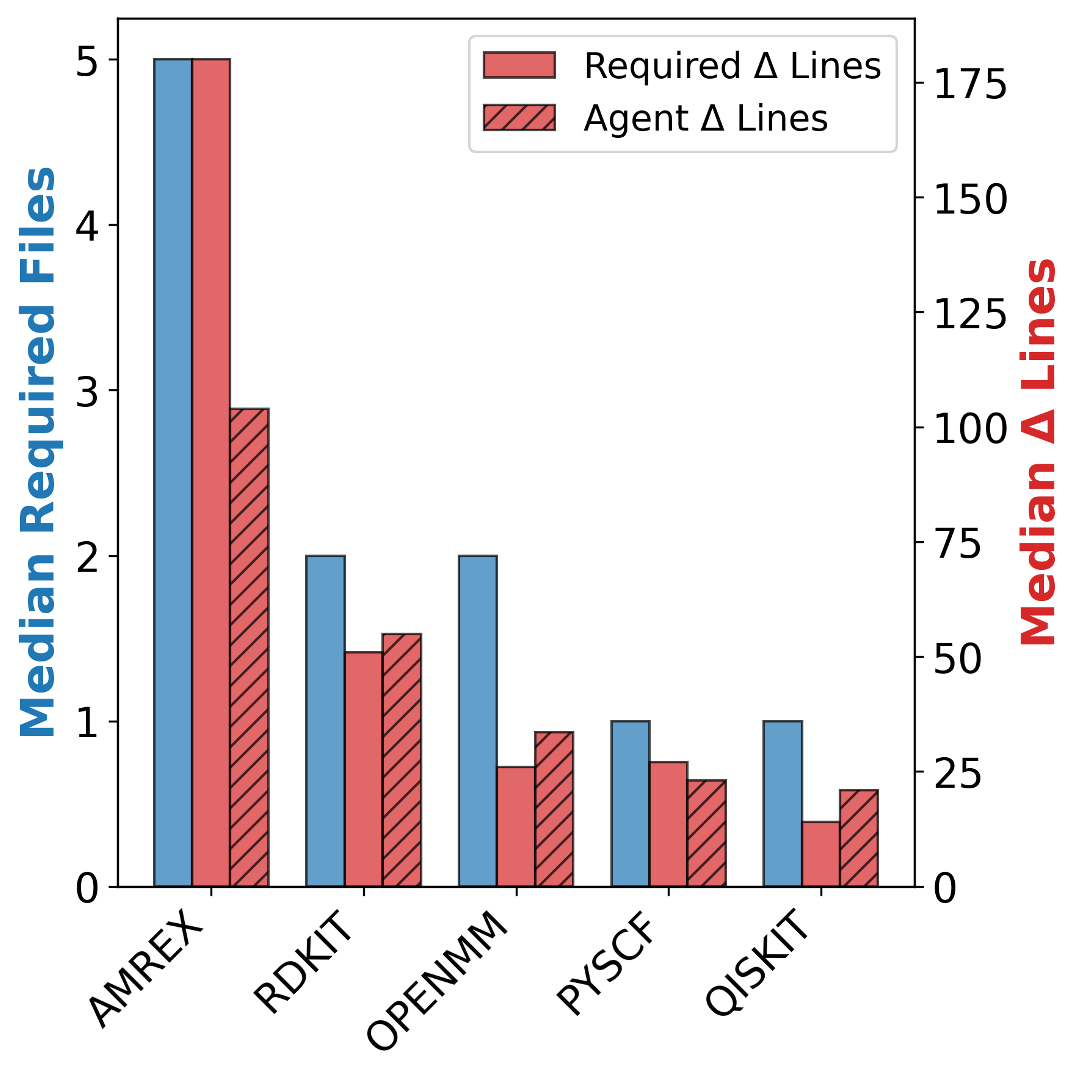

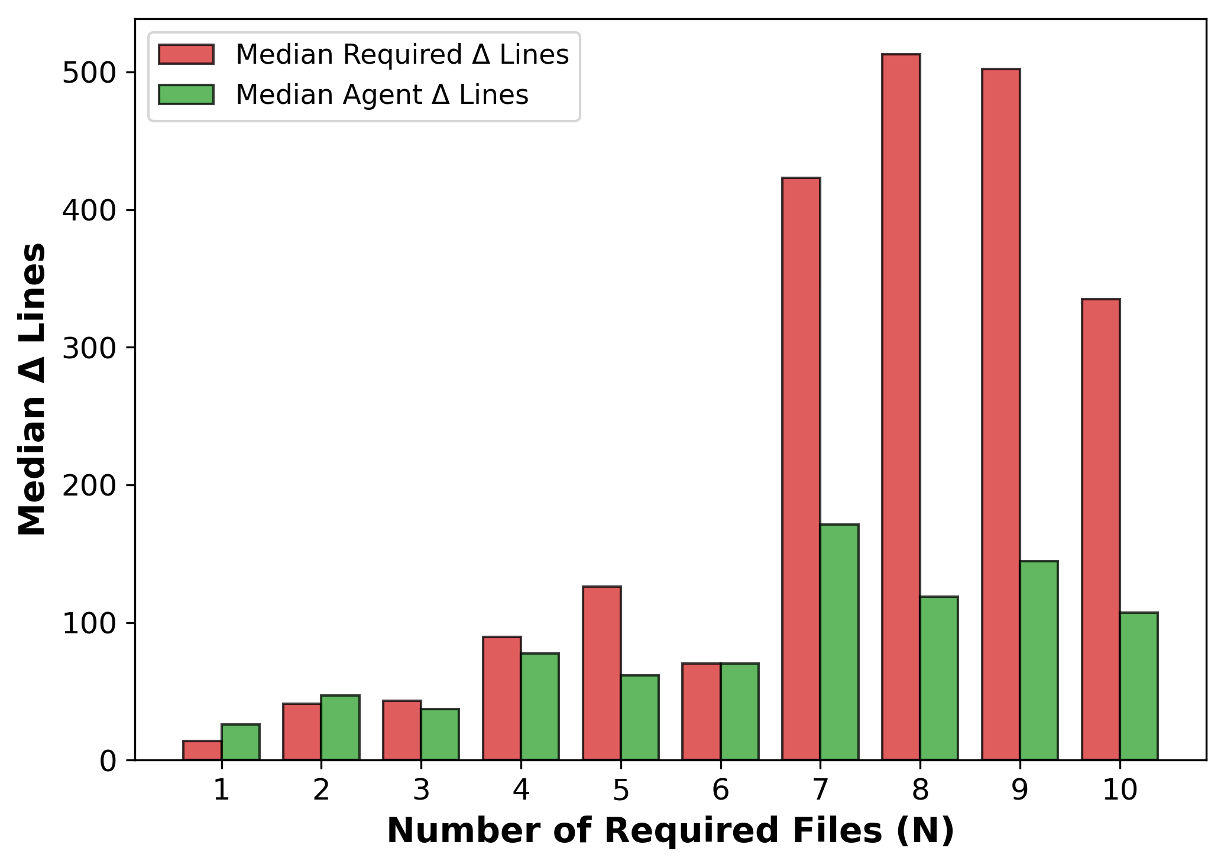

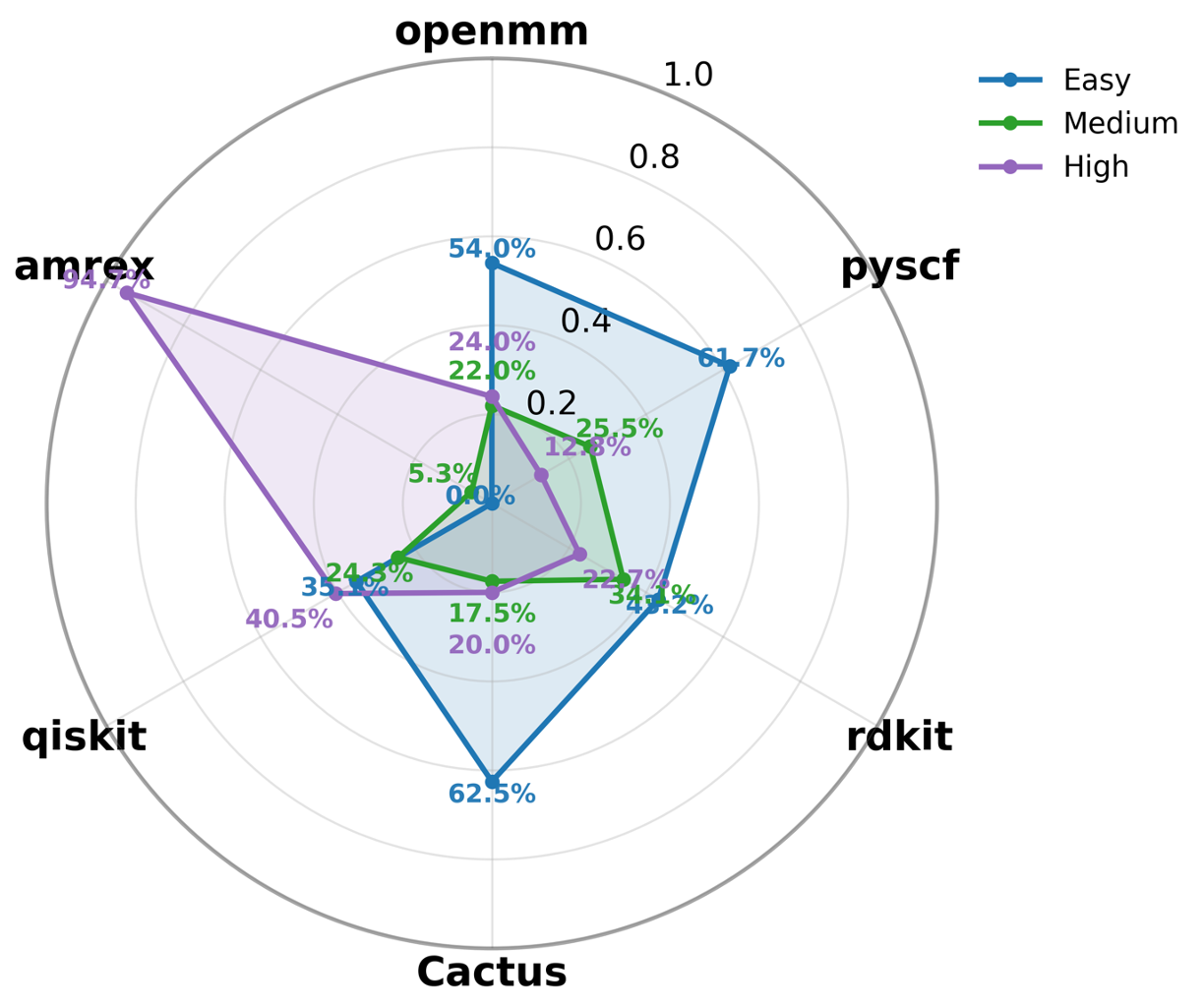

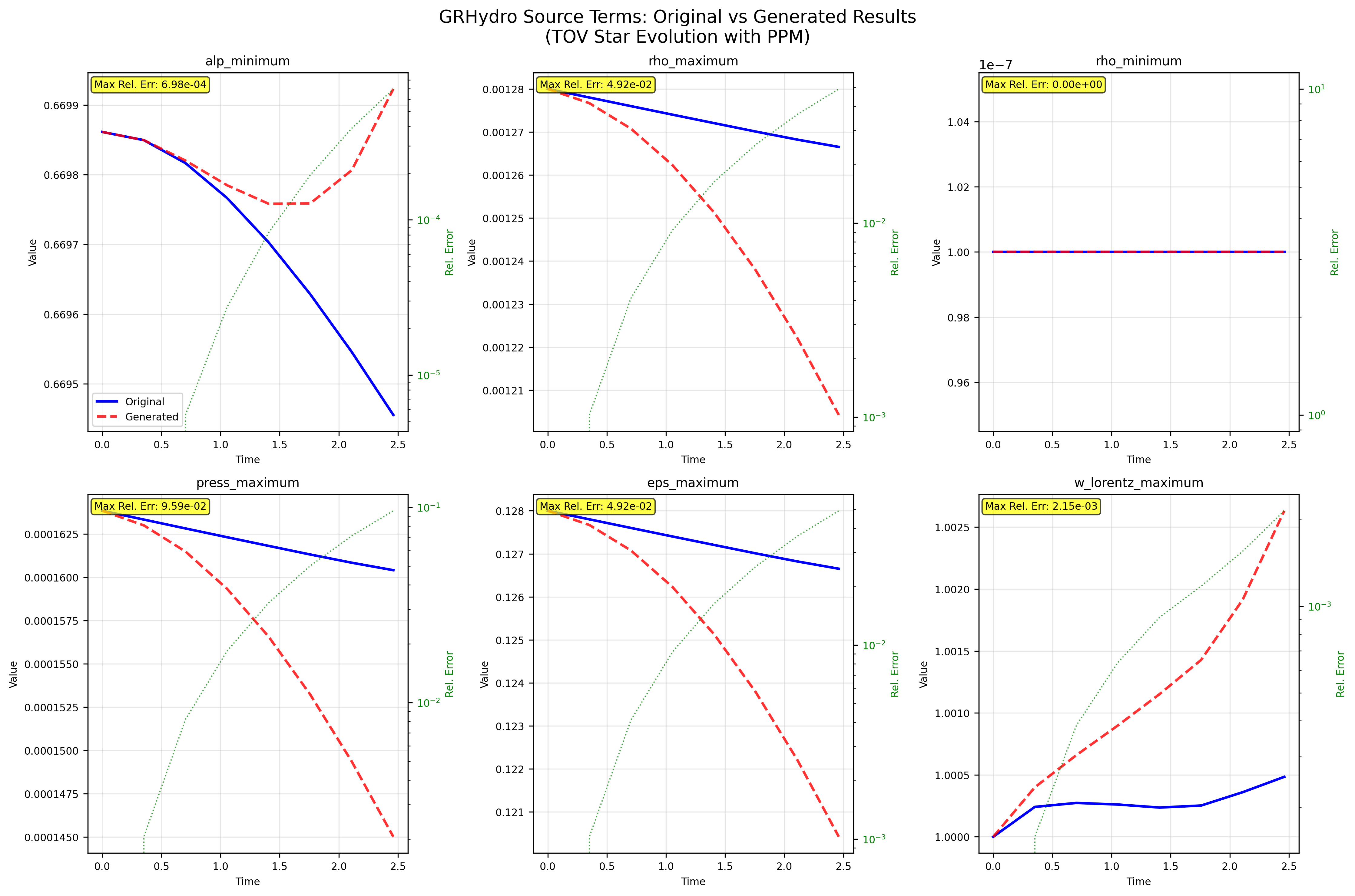

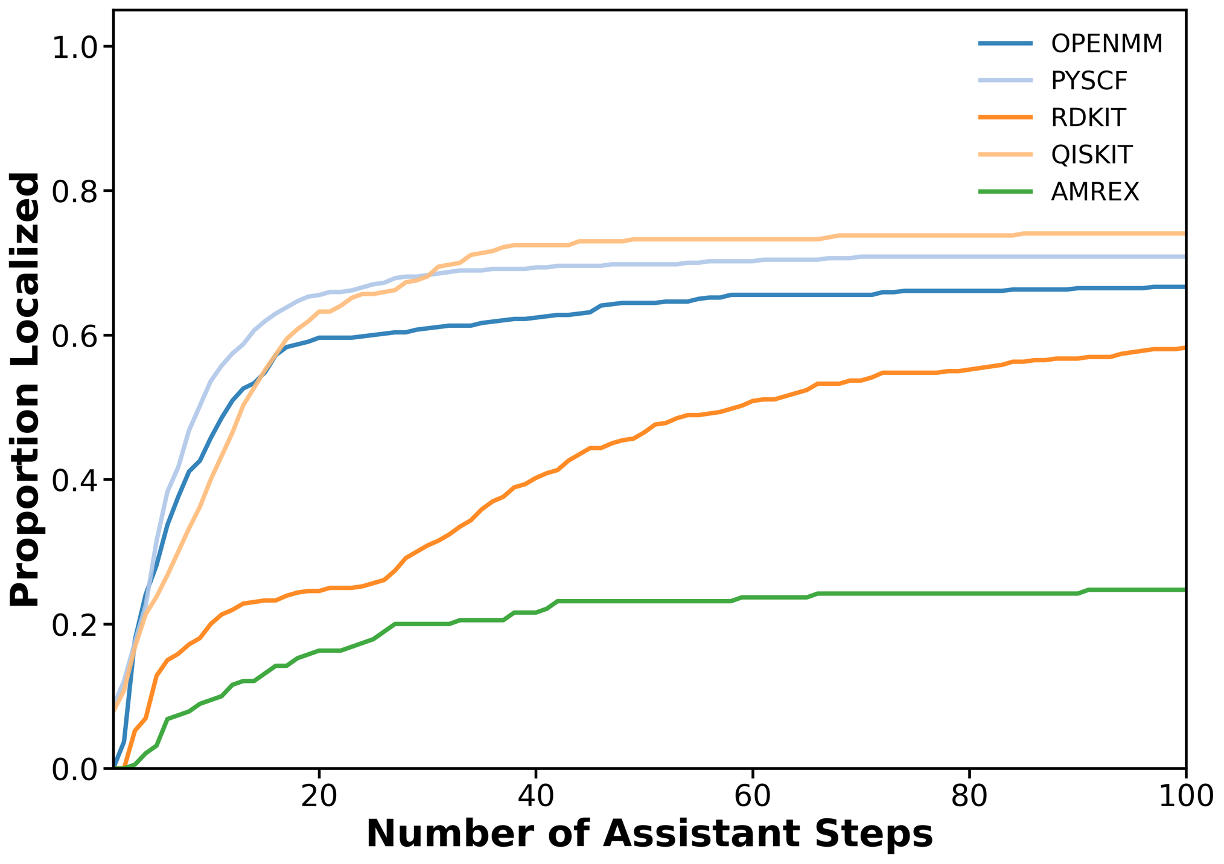

To address this gap, we introduce AInsteinBench, a new benchmark designed to evaluate performance in scientific computing development as practiced in real research environments. Rather than extending existing software-engineering benchmarks, AInsteinBench is constructed to measure how well an agent can operate as a scientific researcher working through code: developing, diagnosing, and maintaining computational implementations that embody modern scientific theory. The benchmark is grounded in large, production-grade scientific repositories spanning quantum chemistry (PySCF), quantum computing (Qiskit), cheminformatics (RDKit), fluid dynamics (AMReX), numerical relativity (Einstein Toolkit), and molecular dynamics simulation (OpenMM). Unlike standard software projects, these codebases encode domain-specific scientific structure: from density-functional theory and self-consistent field formulations to symplectic integration, constrained optimization, and PDE discretizations. Successfully modifying such systems requires reasoning not only about code, but about the scientific assumptions, invariants, and numerical behavior. By curating tasks from these environments, AInsteinBench moves towards whether models can translate scientific understanding into correct and stable computational practice. This focus aligns the benchmark with the realities of scientific programming, where progress is measured by preserving physical correctness and numerical robustness.

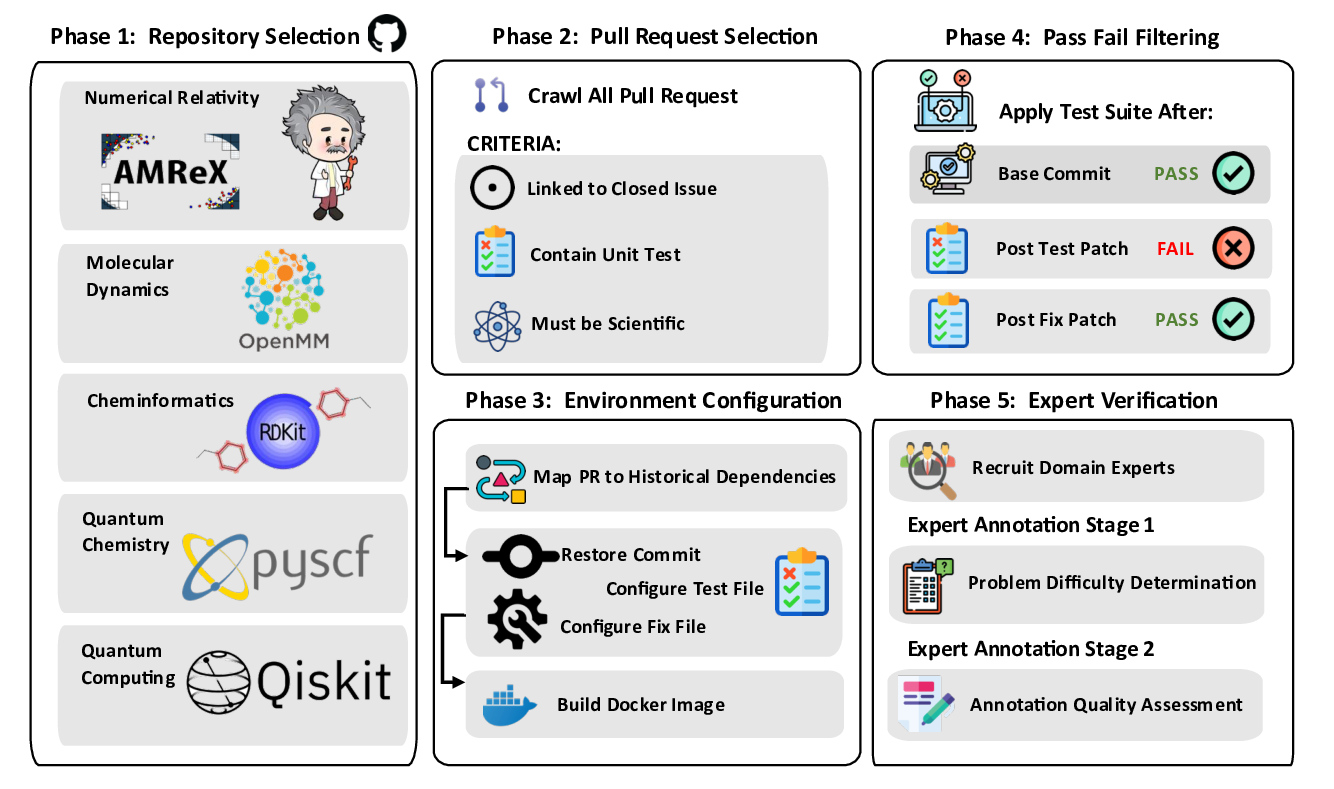

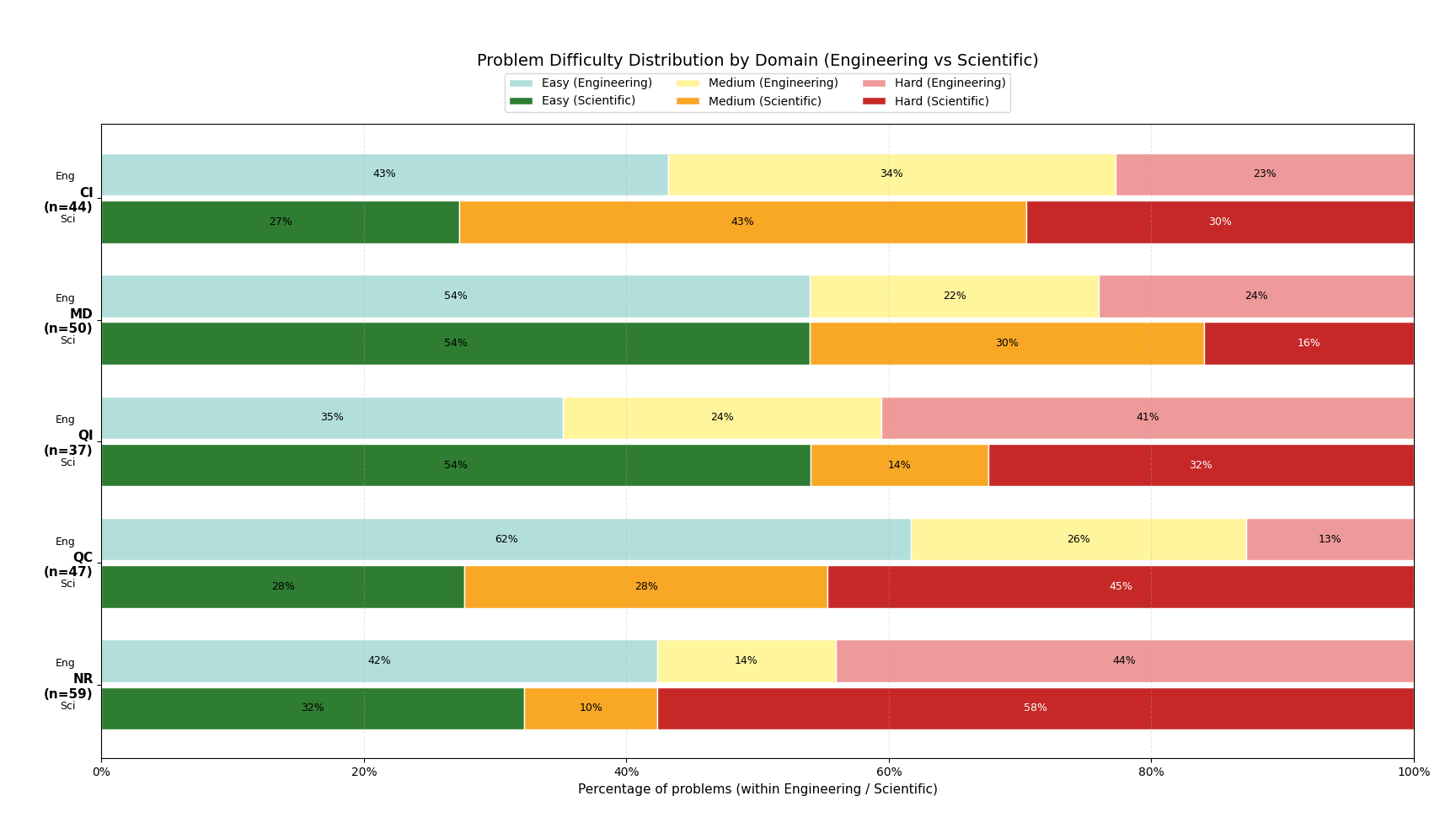

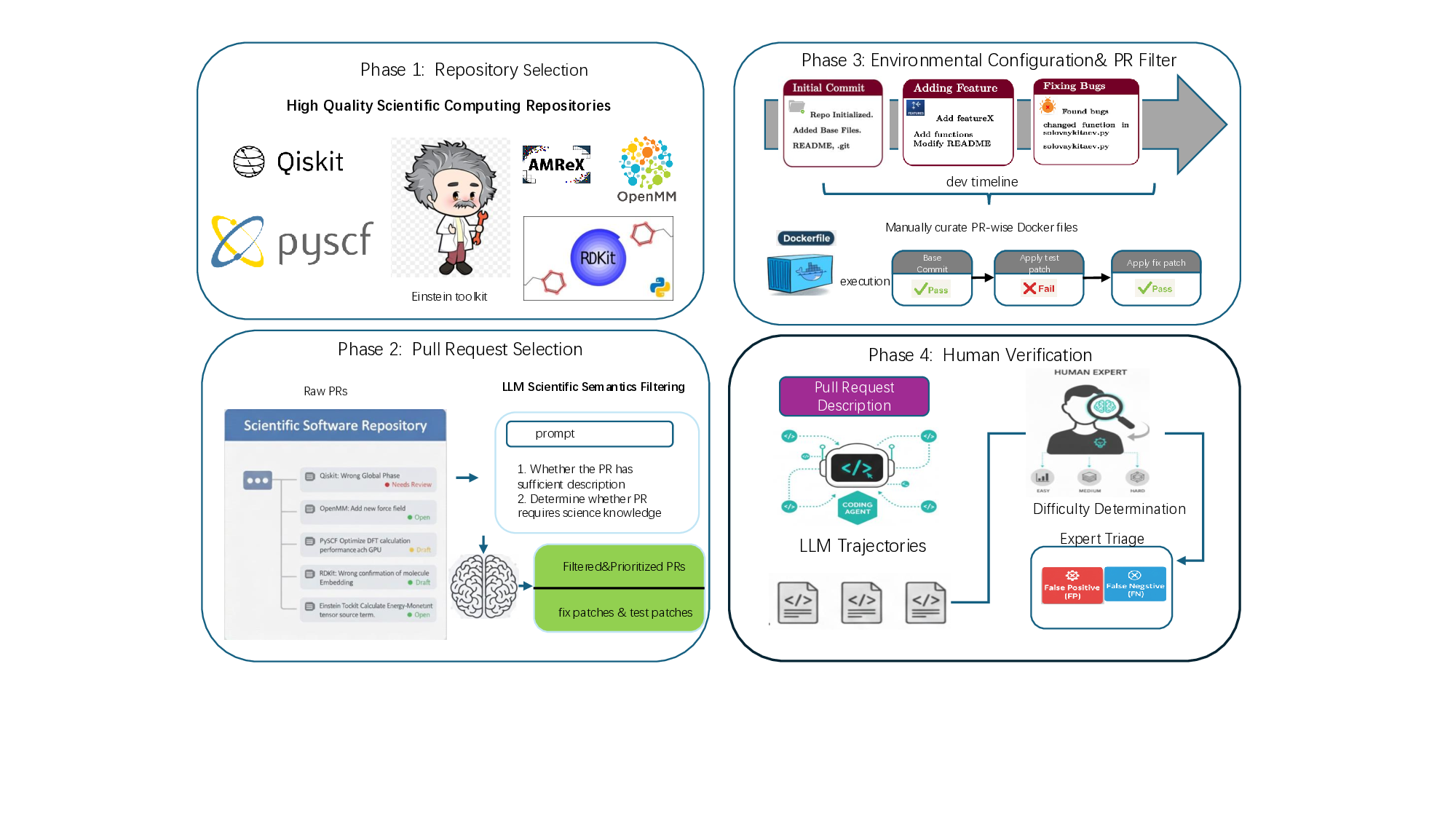

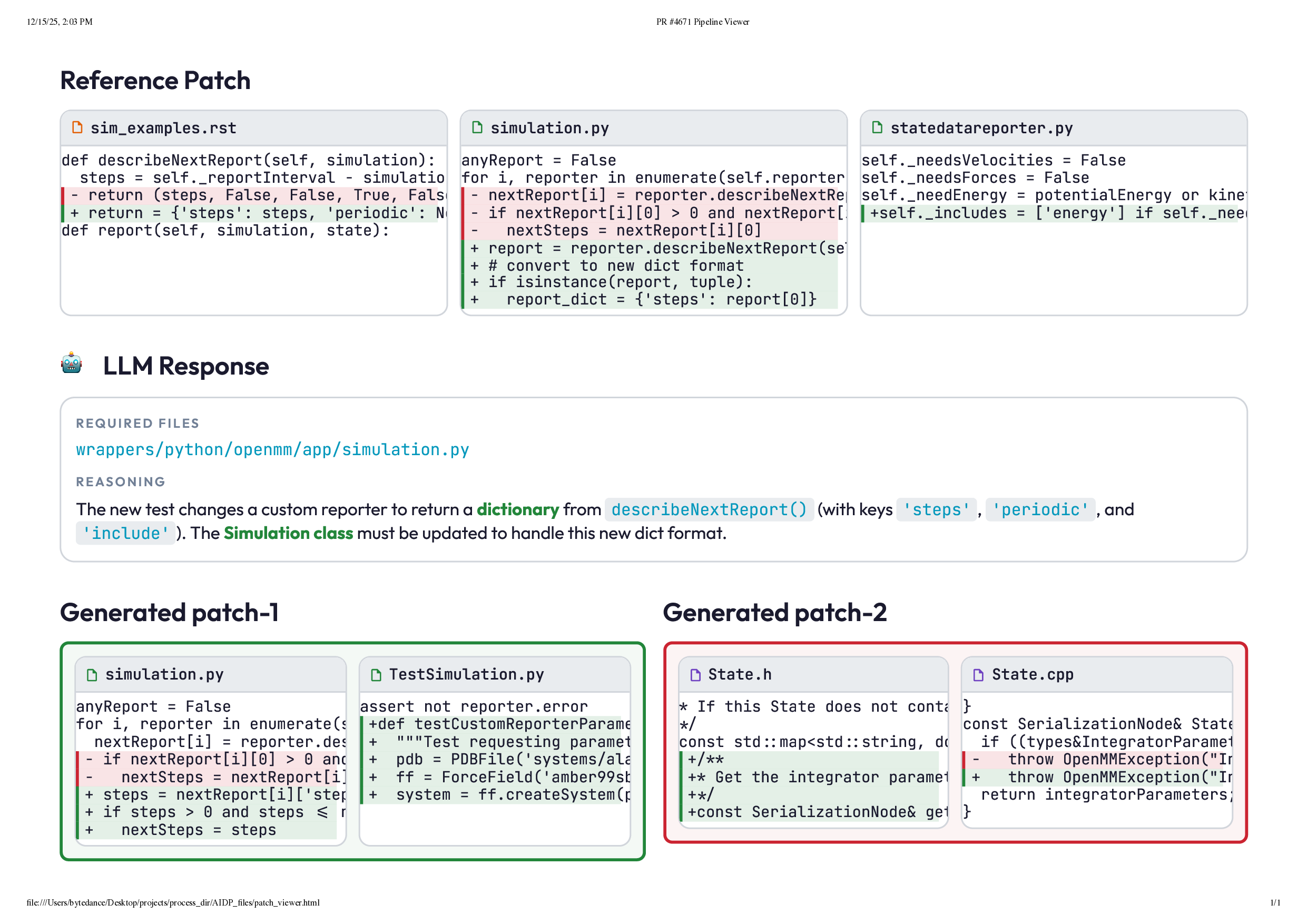

We construct this benchmark through a rigorous multi-phase pipeline inspired by SWE-bench but extended to meet scientific reproducibility standards. First, we identify high-impact scientific repositories with active developer communities and well-maintained test suites, ensuring both scientific relevance and executability. Second, we collect scientifically meaningful issue-linked pull requests and extract before/after code states, environment specifications, and domain-specific metadata. Third, we b

This content is AI-processed based on open access ArXiv data.