We examine the reliability of a widely used clinical AI benchmark whose reference labels were partially generated by LLMs, and find that a substantial fraction are clinically misaligned. We introduce a phased stewardship procedure to amplify the positive impact of physician experts' feedback and then demonstrate, via a controlled RL experiment, how uncaught label bias can materially affect downstream LLM evaluation and alignment. Our results demonstrate that partially LLM-generated labels can embed systemic errors that distort not only evaluation but also downstream model alignment. By adopting a hybrid oversight system, we can prioritize scarce expert feedback to maintain benchmarks as living, clinically-grounded documents. Ensuring this alignment is a prerequisite for the safe deployment of LLMs in high-stakes medical decision support.

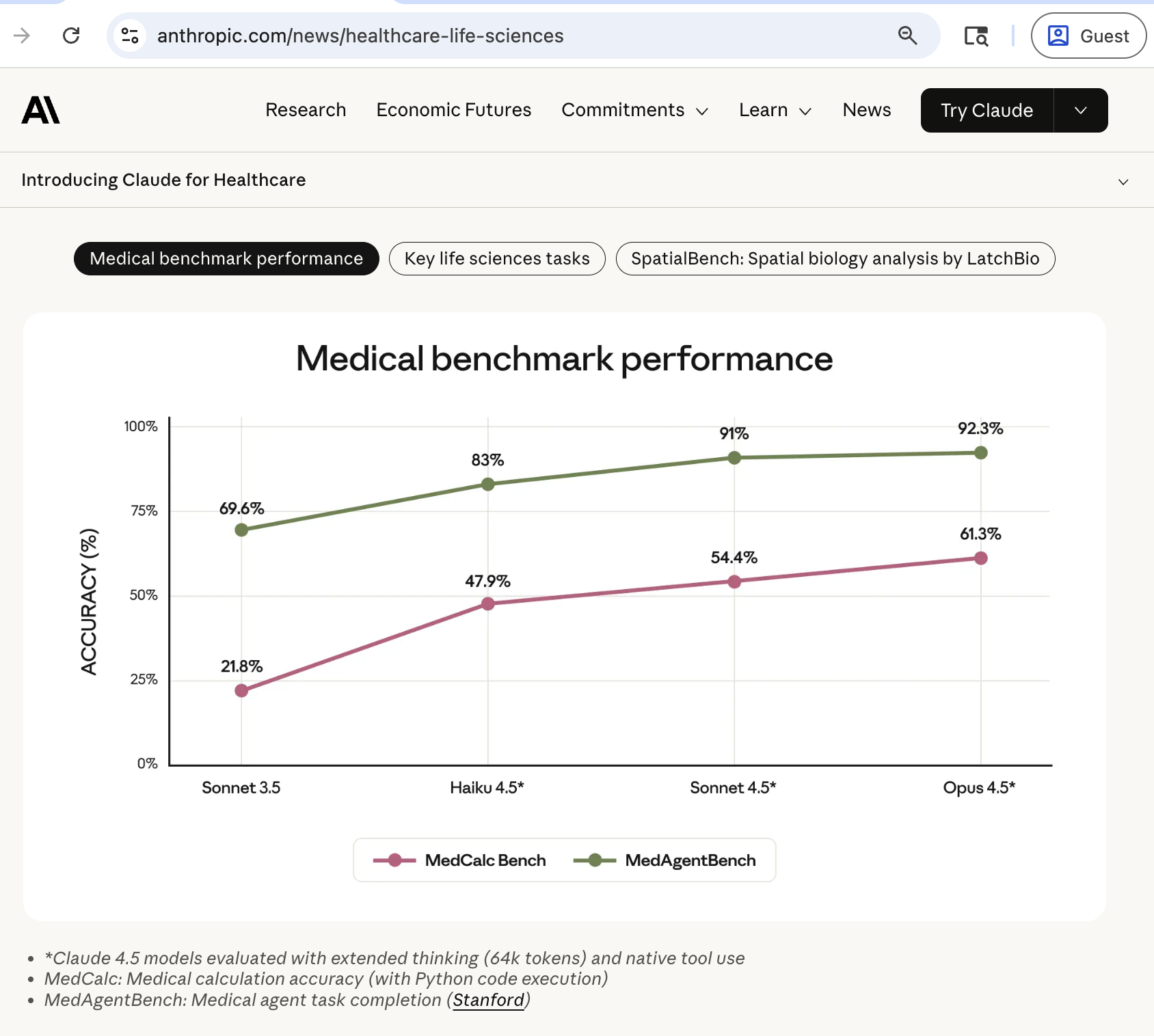

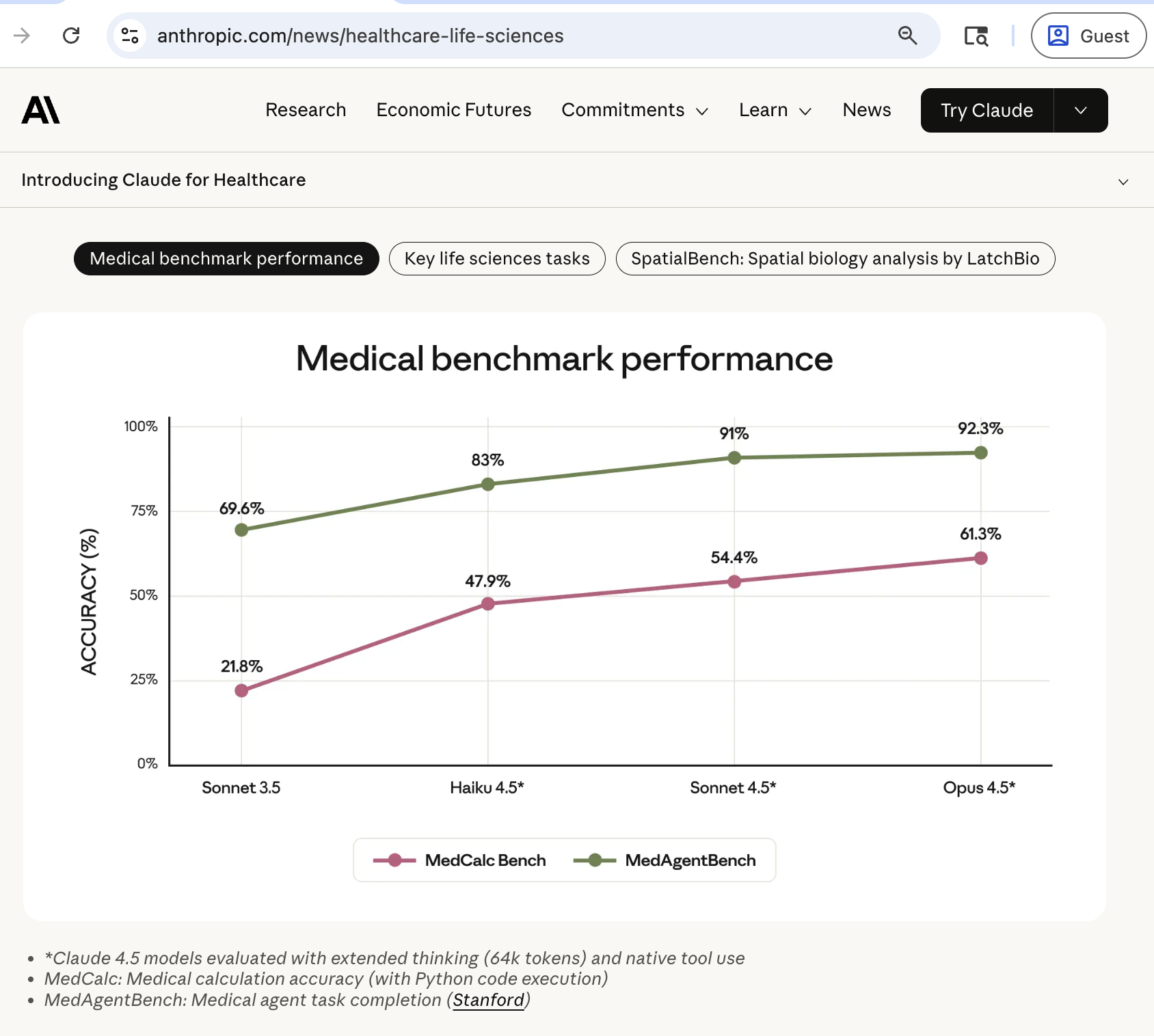

A clinician's day often alternates between patient care, time spent on complex judgment, and time spent on repetitive "information work": retrieving scattered facts from the electronic health record (EHR), reconciling fragmented documentation, and translating that information into standardized actions. This clerical burden contributes to burnout and has been linked to patient-safety and health-system consequences. [1][2][3][4] Tools based on Large Language Models (LLM) are increasingly proposed to reduce this burden, including ambient documentation support and targeted safety guardrails in healthcare delivery. [5][6][7][8][9] Routine computation of medical risk and severity scores is another common information processing scenario that appears suitable for automation. Risk scores such as LACE, CURB-65, and CHA 2 DS 2 -VASc condense patient history, vital signs, and laboratory results into numeric values that inform triage, admission planning, and preventive therapy; 10-12 a worked out example in Supplementary Appendix §D.1 illustrates a computation routine. In practice, clinicians extract criteria from narrative notes or structured EHR data, and then manually calculate the final scores or enter information into calculators such as MDCalc. 13 Manual extraction is time-consuming and error-prone, motivating the adoption of large language model (LLM) systems that can read notes and compute scores end-to-end. As these automated systems are developed, evaluating their efficacy in a scalable but also clinically aligned manner becomes a safety challenge: how do we responsibly verify that they compute scores as accurately as would a conscientious human physician? Public task benchmarks are an important first step for transparency and reproducibility, but large-scale benchmark construction is increasingly assisted by LLMs themselves through feature extraction and normalization. As a prime example, MedCalc-Bench [14] is a widely used large-scale public benchmark for end-to-end medical risk score computation. Besides popularity in academic research, [15][16][17][18][19][20] it was one of two medical benchmarks evaluated on by Anthropic in its recent launch of the "Claude for Healthcare" initiative. 21,22 MedCalc-Bench was constructed from de-identified PubMed Central case reports paired with 55 commonly-used medical calculators on MDCalc. Its original labeling pipeline used GPT-4 for feature extraction and scripted aggregation for final score computation. This automated labeling pipeline yielded a large task dataset of 11,000 labeled instances. The scale and comprehensive calculator coverage of MedCalc-Bench make it an important contribution to clinical natural language processing (NLP) research, as AI model training is inherently data-hungry. Manually producing benchmark labels at this scale is difficult, as sample-bysample clinician adjudication is slower and much more expensive than LLM API calls: sizes of fully physician-labeled medical score datasets, such as [23] and [24], are in the scale of low hundreds. However, the expediency introduces a structural vulnerability: labels can inherit systemic failure modes of the language models, tools, and procedural assumptions used to produce reference labels. It is a concerning situation because in effect, these synthesized benchmark labels are not only the "ground truth" used to measure progress and, increasingly, also a target distribution for AI developers to align their models towards, for example via reinforcement learning (RL). 25,26 When the same labels are reused as RL reward signals, label errors are no longer only measurement noise: they can actively shape the behavior of future models, turning the benchmark from a miscalibrated yardstick into a biased teacher.

In this paper, we audit and improve the clinical soundness of reference labels originally released by MedCalc-Bench in its NeurIPS 2024 publication. 14 Schematically, we propose a scal-able stewardship protocol in which agentic LLM pipelines-LLM-based verifiers instructed to follow a structured checklist and use tools such as search and computation-audit existing labels and independently recompute scores; automated triage then concentrates scarce physician time on the highest-impact disagreements. Physician review resolves contention and identifies truly unanswerable or mismatched note-question pairs, for which abstention (e.g., “unknown”) is safer than forced computation. Importantly, our goal is not to fault the creators of MedCalc-Bench; rather, we use their original dataset release as a motivating case study to develop a transparent, repeatable stewardship process for benchmarks that increasingly influence both evaluation and post-training. Our contributions are as follows:

• Propose systematic stewardship for clinical workflow benchmarks as safety infrastructure and describe the risks of treating partially LLM-generated labels as static oracles.

• Introduce a physician-in-the-loop protocol that comb

This content is AI-processed based on open access ArXiv data.