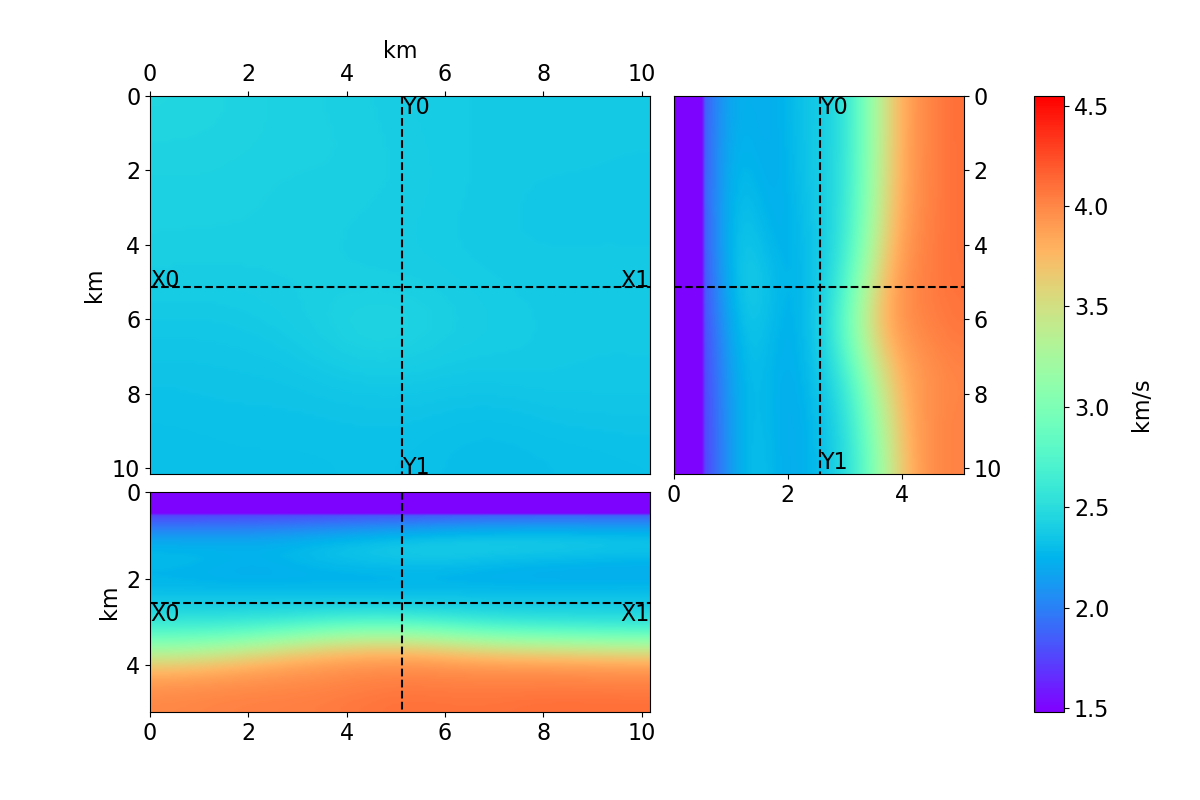

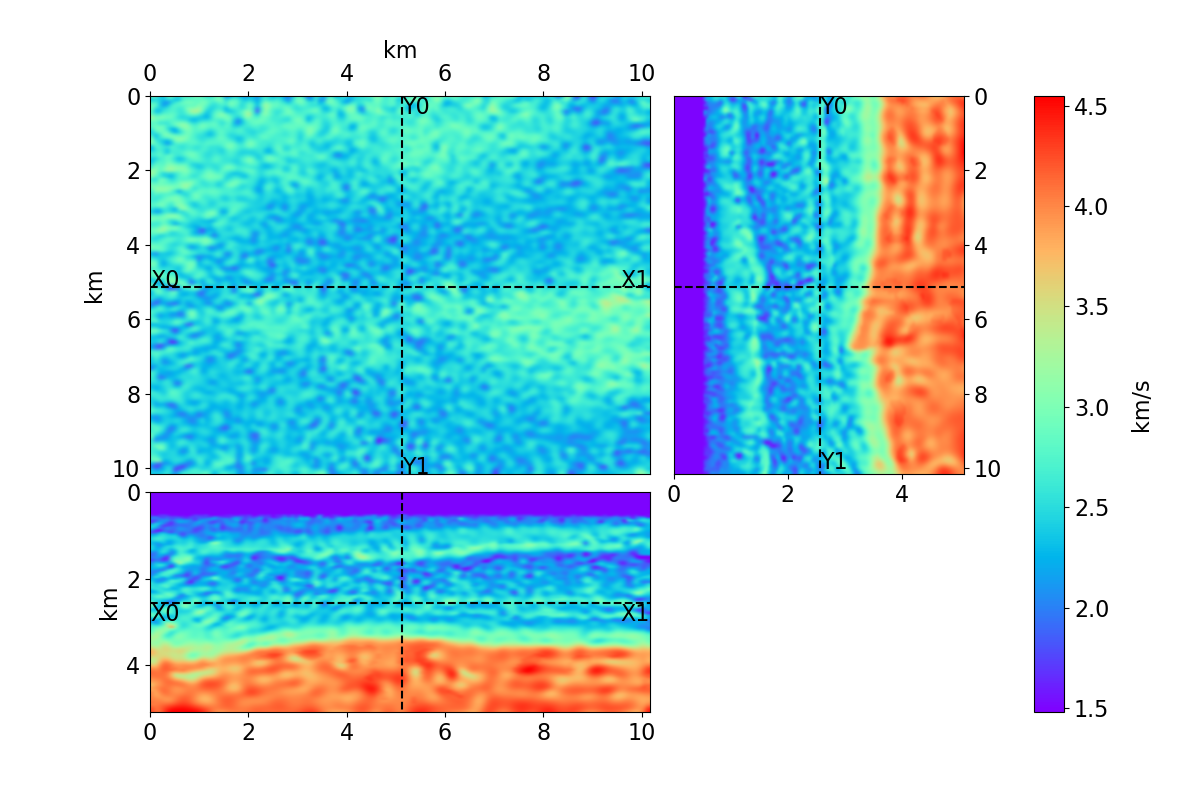

Bayesian full waveform inversion (FWI) offers uncertainty-aware subsurface models; however, posterior sampling directly on observed seismic shot records is rarely practical at the field scale because each sample requires numerous wave-equation solves. We aim to make such sampling feasible for large surveys while preserving calibration, that is, high uncertainty in less illuminated areas. Our approach couples diffusion-based posterior sampling with simultaneous-source FWI data. At each diffusion noise level, a network predicts a clean velocity model. We then apply a stochastic refinement step in model space using Langevin dynamics under the wave-equation likelihood and reintroduce noise to decouple successive levels before proceeding. Simultaneous-source batches reduce forward and adjoint solves approximately in proportion to the supergather size, while an unconditional diffusion prior trained on velocity patches and volumes helps suppress source-related numerical artefacts. We evaluate the method on three 2D synthetic datasets (SEG/EAGE Overthrust, SEG/EAGE Salt, SEAM Arid), a 2D field line, and a 3D upscaling study. Relative to a particle-based variational baseline, namely Stein variational gradient descent without a learned prior and with single-source (non-simultaneous-source) FWI, our sampler achieves lower model error and better data fit at a substantially reduced computational cost. By aligning encoded-shot likelihoods with diffusion-based sampling and exploiting straightforward parallelization over samples and source batches, the method provides a practical path to calibrated posterior inference on observed shot records that scales to large 2D and 3D problems.

Full waveform inversion (FWI) embodies the state-of-the-art (SOTA) framework for seismic velocity model building. This iterative optimization process aims to extract a high-resolution subsurface velocity model by minimizing the discrepancy between observed and simulated data governed by the wave equation [1,2]. Yet, the very features that make FWI so compelling also attract practical challenges: severe nonlinearity and cycle skipping when low frequencies are scarce, incomplete illumination, and the high computational burden of repeatedly solving large forward/adjoint problems across many shots. One potential way to temper the cost is to encode or combine shots so that one wavefield evaluation stands in for many; however, the resulting simultaneous-sources crosstalk must be managed throughout the inversion [3,4,5,6]. In practice, this sets up a simple trade-off: encoding cuts cost by performing simultaneous simulations across multiple shots, but the mixing (crosstalk) can leak into the model unless we restrain it. This motivates a Bayesian treatment that quantifies and explores the null space of the solution-where multiple geologically plausible models explain the observed seismic data-through posterior samples and uncertainty maps.

A Bayesian formulation places a prior on the model and defines a likelihood using the wave equation [7,8]; in practice, we access this through the adjoint-state (FWI) gradient of the log-likelihood and thus perform posterior inference via gradient information. Particle transports such as the Stein variational gradient descent (SVGD) algorithms are attractive because they move a set of particles toward the posterior using gradients of the log posterior [9], and they have proven practical for large-scale FWI relative to Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) [10,11,12]. Many recent SVGD-for-FWI studies adopt uniform (“null”) priors, so the posterior is largely likelihood-dominated; this simplifies implementation but shifts regularization to algorithmic choices (kernel bandwidth, step schedules) and box bounds, which can be mode-seeking and under-estimate posterior variance in ill-posed regimes [13,14]. Likelihood annealing-i.e., tempering the data term by a factor β ∈ [0, 1] and increasing β over stages-can stabilize updates, and carefully designed wave-equation perturbations can aid exploration [15]. However, neither tactic changes the main cost driver: each update still requires full-shot adjoint-state gradients, and with a null prior, the inference remains likelihood-dominated and sensitive to cycle skipping. This motivates a formulation that (i) reduces per-iteration PDE cost via simultaneous (encoded) shots, and (ii) injects a learned prior so uncertainty is governed by both data and geology rather than by algorithmic heuristics alone.

Deep generative priors offer a complementary path. In Plug-and-Play (PnP) [16] and Regularization by Denoising (RED) [17], a learned denoiser provides a powerful, data-driven regularizer inside an optimization loop. Building on this idea, several works have used unconditional diffusion models as learned priors for deterministic FWI and reported higher-quality velocity reconstructions and better data fits than classical penalties [18,19,20], complementing conventional regularization theory [21,22]. Beyond unconditional priors, controllable or conditional variants inject auxiliary information to steer the generated geology [23]; for example, [24] conditions a diffusion generator on common-image-gathers to perform variational inference, while [25] explores a latent diffusion model that maps directly from measured shot gathers to velocity via a shared latent representation. Taken together, these strands mainly deliver either point estimates (regularized optimization) or amortized reconstructions. The latter entails that the generated samples may be plausible, but do not necessarily fit the observed seismic data. To move from regularized reconstruction to explicit posterior sampling with diffusion priors and common-shot gathers data, we turn next to diffusion-based samplers that incorporate measurement information during inference.

To perform posterior sampling with diffusion models as prior, [26] introduced the Denoising Diffusion Restoration Models (DDRM) for linear inverse problems with closed-form conditioning. For general nonlinear settings, [27] introduced the Diffusion Posterior Sampling (DPS) by guiding the reverse process with likelihood information. [28] introduced the decoupled annealed posterior sampling (DAPS), extending the DPS framework by decoupling the consecutive steps in the DPS updates with stochastic refinement steps, and showed better posterior sampling exploration and quality. These methods, however, are typically evaluated where the forward operator is cheap or linear (e.g., seismic inversion [29]). In contrast, FWI embeds an expensive, nonlinear relationship between the model and data, which is computationally more demanding by a

This content is AI-processed based on open access ArXiv data.